In developed countries, it is estimated that 1–2 % of the adult population has heart failure (HF), with the prevalence increasing to more than 10 % in those aged >70 years.1 Despite advances in therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), it remains a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality, punctuated by episodes of unplanned hospitalisation.2

HF is one of the commonest causes of unscheduled hospital admissions3 and data consistently show a lower uptake of evidencebased investigations and therapies in adults >75 years as well as higher HF-related mortality.4 Mortality and rehospitalisation rates are higher amongst patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities than those going home.5 Older patients more frequently experience comorbidities, frailty, polypharmacy and cognitive impairment and these factors have a significant impact on outcomes. These aspects require proper evaluation to best assess and plan patients’ long-termcare needs.

In this review, we examine HF-care planning in relation to older patients. While current guidance has its limitations, we offer here a pragmatic approach to care planning in this patient population.

Care Planning in Skilled Nursing Facilities

While the majority of older people live at home alone, or with carers, in the UK 16 % of people aged >85 years live in care homes.6 The spectrum of care ranges from sheltered housing to a variety of assisted living facilities, residential and nursing homes. The reported prevalence of HF in nursing homes ranges from 20.0 to 37.4 %.7 The Heart Failure in Care Homes (HFinCH) study8 found a higher prevalence of HF in UK care-facility residents aged 65–100 years than in community populations. Most cases were previously undiagnosed and three-quarters of previously recorded cases were unconfirmed using the latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, echocardiogram and brain natriuretic peptide measurements.

Furthermore, they found that the common symptoms and signs appeared to have little clinical utility in this population. A study of Canadian long-term-care residents >65 years found the use of evidence-based therapies appeared to be low, and not adequately explained by drug contraindications or advance directives.9 Monitoring of weight was performed infrequently and echocardiogram evaluation of left ventricle function under-utilised.10

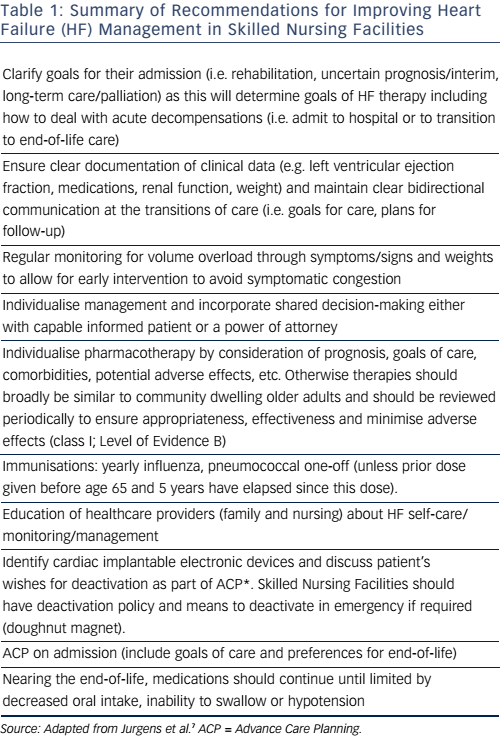

That evidence-based medical therapies can improve outcomes (including incidence of hospitalisations) is the cornerstone of modern medicine, but the benefits of evidence-based care for institutionalised older people are less well understood. It is clear that HF patients discharged to long-term-care facilities are at higher risk of adverse events than those discharged home (whether with home health services or self-caring). Higher rates of rehospitalisation and 1-year mortality rates >50 % have been reported in this group.5 Given the reported under-utilisation of therapies and poor monitoring of volume overload, such poor outcomes require attention. Accordingly, the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America (AHA/HFSA) have issued a scientific statement with the aim of improving HF management in Skilled Nursing Facilities.7 This is a detailed document and Table 1 summarises some of the key recommendations related to care planning.

With the exception of the recommendation on pharmacotherapy, most of the AHA/HFSA recommendations have a class I treatment effect (i.e. should be performed because benefit clearly outweighs risk) but only reach level C evidence (i.e. very limited population evaluated and recommendations reached by consensus opinion of experts).

The level C evidence rating is understandable given that frailer, functionally and cognitively impaired patients are often excluded from large randomised controlled trials, which provide much of the evidence base. Injudicious application of treatment guidelines may not result in better outcomes for these patients in whom competing comorbidity may have a large impact on prognosis. A tailored and individualised approach to goal setting and care planning is necessary. This requires an understanding of how HF presents in older people, as well as an awareness of how comorbidities impact on standard management. After reviewing these issues, we will then discuss strategies for managing them, including an overview of multidisciplinary team work, comprehensive geriatric assessment and palliative, supportive and end-of-life care.

Non-specific Presentation

Firstly, like many conditions in the elderly, HF may present with atypical features, for example, loss of appetite or decrease in body mass index, whilst traditional HF symptoms such as dyspnoea or oedema may be absent and lack specificity.11 This can result in delayed investigation and diagnosis.

Another difference is the increased prevalence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), especially in elderly women.12 This compounds some of the challenges in managing elderly patients because, to date, this is a condition with no treatment proven to alter outcomes.

Comorbidities

It is important to bear in mind that most randomised controlled trials in HF specifically exclude patients with significant comorbidities or HFpEF, yet this group constitutes a significant proportion of older people with HF.4 Up to 75 % of >65 year olds will have multiple chronic conditions that will impact HF management;13 comorbidity is one of the strongest independent predictors of rehospitalisation and mortality.14 Comorbidites can also confound early detection of HF; for example, osteoarthritis and difficulties mobilising may limit the patient before exertional dyspnoea is reported.15

Renal impairment, anaemia, atrial fibrillation, malignancy, cerebrovascular disease and orthostatic hypotension are all more common in older patients than younger patients and impact management and outcomes. These comorbidities increase the likelihood of polypharmacy as well as making drug-related side-effects more common. Polypharmacy itself, whilst often a result of well-intentioned and appropriate treatment of multiple comorbidites, is independently associated with poor outcomes; for example >4 different medications per day increases the risk of falling as well as the risk of recurrent falls.16 This is particularly important to consider given the relatively poor evidence base specifically applicable to this older comorbid population.

Two key factors less frequently considered as comorbidities in patients with HF are cognitive impairment and frailty. In clinical practice, they are significant players and worthy of more in depth consideration.

Cognitive Impairment

A recent review of cognitive impairment in HF reported an estimated prevalence between 30 and 80 %, with the wide range due to differences in study design, case mix and the types of cognitive assessments used.17 An independent association with increasing severity of disease (whether quantified by ejection fraction or symptom burden) and poorer cognition was also described.

From our own experience, the authors also recognise a high prevalence of delirium among older HF patients. One study estimated delirium was present in 17 % of patients with unscheduled HF hospitalisations.18

What is clear is that both dementia and delirium are associated with poorer clinical outcomes, with longer duration of hospitalisation and increased inpatient and 1-year mortality.19,20

Impaired cognitive function is associated with poor levels of selfcare and functional decline21 and predicts non-engagement in HF management programmes. Patients may not recognise or understand a change in symptoms or function, with negative consequences for overall care.

Identifying cognitive impairment allows patient, carers and clinicians to plan bespoke management strategies and clinicians should be vigilant for its presence. Observational data suggest that informal assessment of cognition by cardiologists is insensitive, with approximately three in four HF patients with important cognitive problems not recognised as such during their routine consultations.22 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidance for chronic heart failure management in which they advise all patients have a clinical assessment of cognitive status.23 Although not a formal recommendation, the ESC suggest that cognitive function be assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA).1 However, their recommendation of these assessments are not specific to HF and a recent systematic review concluded that the accuracy of normative values for these tests in HF need to be established,24 work that is currently underway by the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (http:// dementia.cochrane.org/). Locally, the authors use the 4AT (see www. the4AT.com) as a quick screening tool for cognitive impairment and delirium.25 This is a validated tool routinely used in clinical practice internationally to detect delirium with good sensitivity and specificity. Its benefits are that it takes only 2 minutes to administer and no special training is required.

As yet, there are no specific medical treatments or approaches to care that have been shown to prevent cognitive decline in those with early dementia or pre-dementia syndromes; this includes interventions that aim to minimise the vascular component of cognitive decline26 and treatments targeting underlying neurochemical abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease, such as acetylcholinestase inhibitors.27 Modifiable lifestyle risk-factors for dementia (such as smoking, excessive alcohol, sedentary lifestyle and diet) should be reviewed in patients with early dementia and, if appropriate, actively managed to prevent cognitive decline.28

In practice, regular review by a multidisciplinary HF team is required to evaluate clinical condition and medication tolerance. Collaboration with specialist dementia support teams is helpful because some patients do benefit from cognitive enhancers; however, acetylcholinestase inhibitors must be used with caution owing to the risk of bradycardia, sick sinus syndrome or other arrhythmias resulting from QT prolongation. Medication compliance aids, tailored self-care advice and involvement of family and/or caregivers can all improve adherence with complex HF medication and self-care regimens.1

We can find no good data to suggest standard HF therapy is harmful in patients with cognitive impairment and, given clear evidence of benefit in ‘fitter’ older patients, the best approach is to consider evidence-based treatments for all HF patients but individualise to take account of comorbidites or goals; for example, using digoxin sparingly to limit its potential for toxicity owing to decreased renal clearance with ageing. Another example from clinical practice is compromising on ‘study targets’ of beta blockers to accommodate the cognitive enhancer donepezil where the latter agent had produced benefits in cognition and function that a patient or caregiver valued more highly than potential life prolongation.

Frailty

The concept of frailty is an important one for all professionals engaged in HF care to grasp. Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome characterised by increased vulnerability to stressors, occurring as a result of a cumulative decline in different physiological systems occurring during a lifetime.29 It is associated with increased risk of falls, hospitalisation, nursing home admission and mortality, with poorer outcomes seen for increasing severity of frailty.30,31

High prevalence of frailty has been reported in older patients with HF, with one study documenting its presence in >70 % patients >80 years old.32

Identifying which HF patients are frail is important for improving outcomes and avoiding unnecessary harm. Non-specific symptoms of fatigue that can signify progressive HF in older people must be differentiated from frailty because the former may be reversible with treatment. The use of objective tools to measure frailty can help with this (discussed in more detail below). In addition,frailty should be factored into decision-making about procedural therapies (e.g. how well a patient might tolerate surgery and the likely benefit of the intervention). Finally, upon identification, frailty should indicate those patients who need closer contact with the HF specialist team and who would benefit from comprehensive geriatric assessment.

There are two broad models of frailty: the Frailty Phenotype records multiple components of the syndrome (unintentional weight loss, weak grip strength, slow gait speed, physical inactivity and self-reported exhaustion), with frailty present in patients with three or more of these characteristics.33 The second model is the cumulative health deficit model first described by Rockwood.34 Both are too cumbersome for routine clinical practice. Following a review of the diagnostic accuracy of simple screening tests for frailty35, the British Geriatric Society recommends the use the timed-up-and-go test (with a cut off score of 10 seconds to get up from a chair, walk 3 metres, turn round and sit down) or gait speed (taking more than 5 seconds to walk 4 metres using usual walking aids if appropriate).36 Several HF trials have confirmed gait speed as a strong predictor of mortality, morbidity and re-hospitalisation in HF patients.37–39

The ESC have specific recommendations regarding monitoring and follow-up of the older adult with HF, including the monitoring of frailty along with addressing its reversible causes (both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular).1 In many frail older patients, poor symptom control results in reduced exercise tolerance, which in turn leads to underused skeletal muscle and sarcopenia, thus accelerating a functional decline.40 The key to preventing advancing frailty in this patient group is to optimise symptom control, reduce frequency of HF exacerbations and maintain activity as best as able in each patient. Level 1 guideline supports the benefits of exercise training to improve functional capacity, quality of life, hospitalisations and survival in HF patients.13

In a Cochrane review of exercise interventions for long-term-care residents (a group who are likely to include the frailest elderly), strength and balance training successfully increased muscle strength and functional abilities.41 The most effective intensity (duration and frequency) of exercise intervention remains uncertain but it is encouraging that even small gains in strength can translate into important functional gains. Other than correcting vitamin D insufficiency and optimising protein intake, there is limited evidence for specific nutritional interventions.36

As we will discuss later, comprehensive geriatric assessment provides a robust method of managing these types of patients.42

Strategies for Management

Understanding these comorbidities is important for planning care for older patients. As discussed earlier, the scientific statement on HF management in skilled nursing facilities provides details on specific clinical areas to be reviewed (see Table 1) but we also feel it is important to review the systems of care planning that are known to improve outcomes for older adults, notably multidisciplinary team work and comprehensive geriatric assessment.

Multidisciplinary Team Work

Up to 25 % of patients hospitalised with HF are readmitted again within 30 days of discharge; only 35 % of these readmissions are for HF, with the remainder for diverse indications (renal impairment, pneumonia and arrhythmias).43 Failure to understand and follow often complex plans of care are thought to contribute to these high rehospitalisation rates. As such, recent guidelines all emphasise the importance of developing a comprehensive plan of care using a multidisciplinary care team approach.

McAlister et al. were one of the first groups to systematically review the evidence for systems of care for HF patients. Their work showed that follow-up by a specialist multidisciplinary team reduced mortality, HF hospitalisation and all-cause hospitalisations, suggesting the intervention helped manage more than just the patient’s HF.44 More recently, and to clarify which specific aspects of multidisciplinary care provide the most benefit, the Cochrane group performed a systematic review of disease management programs after hospital discharge.45 They identified programs as having eight common components: telephone follow-up, education, self-management, weight monitoring, sodium restriction, exercise recommendations, medication review and social and psychological support. When compared with usual care, clinic care models did not reduce either rehospitalisation or mortality but case management with its early, intense post-discharge monitoring reduced late mortality (>6 months after discharge). HF and all-cause rehospitalisation was reduced in both case management and multidisciplinary care programs. Another study found that reductions in hospitalisation rates were greatest among moderately frail HF patients.46 This study also found that applying a multidimensional assessment was useful to exclude severely frail patients, who require follow-up with intensive, home-based programs. In other words, identifying high-risk patients allows us to target the right treatment.

The importance of multidisciplinary follow-up in HF management has been highlighted by both the American College of Cardiology Foundation and AHA13 and, more recently, the ESC1, who recommend that HF patients be enrolled in multidisciplinary-care management programs to reduce HF hospitalisation and mortality (class I recommendation, evidence level A).

Different HF management programs exist in different countries and healthcare settings but the following list outlines some of the key components (adapted from ESC guidelines1). HF management programmes should:

- employ a multidisciplinary team (cardiologists, primary care physicians, nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, social workers, psychologists, surgeons, geriatricians etc.)

- target high-risk symptomatic patients

- provide regular assessment of (and appropriate intervention in response to) weight changes , nutritional and functional status or laboratory findings.

- facilitate patient education with special emphasis on symptom monitoring to enable self-care and the option of flexible diuretic dosing

- provide follow-up after discharge (either in clinic, home-based visits, telephone support, remote monitoring or a combination thereof)

- have easy access to care during episodes of decompensation

- have access to advance treatment options including device management

- provide psychosocial support to patients and family and/or caregivers

Increased attention is also being given to the transitions of care. A recent scientific statement from the AHA describes how integrated, interdisciplinary transition of care programs can help patients along the continuum of care.47

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Geriatricians use Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) as a robust method for identifying high-risk patients. High CGA scores predict 2-year mortality in HF patients >75 years of age.48 Rodriguez-Pascual et al. calculated participants’ CGA scores based on limitation in activities of daily living, mobility, comorbidities, cognitive impairment and pre-admission number of medications; all components showed a consistent association, with increased risk of death at 2 years.

Though used in HF research mainly as a prognostic tool, CGA is a diagnostic process at the core of a geriatrician’s daily clinical practice. Much like the use of a frailty assessment tool, a CGA should identify which patients need closer contact with the HF specialist team and those who would benefit from assessment by a geriatrician. Using coordinated multidisciplinary assessment and geriatric medicine expertise, a CGA determines the medical, psychological and functional capabilities of an older person to develop an integrated plan for treatment and long-term follow-up.42 Targeted interventions may involve enlisting social support services, discontinuing non-essential medications, adapting the home environment and providing mobility aids, to name but a few.

The Cochrane group reviewed 22 trials that compared CGA to usual care and evaluated 10,315 participants in six countries. Patients admitted to hospital in an emergency who were assessed with CGA were more likely to be alive and in their own homes at 6-months (odds ratio [OR] 1.25; 95 % CI [1.11–1.42]; p<0.001) and 12-month follow-up (OR 1.16; 95 % CI [1.05–1.28]; p=0.003) compared with general medical care. They were less likely to be institutionalised (OR 0.79), die or experience deterioration in their condition (OR 0.76) and more likely to have improved cognition (OR 1.11). Models of CGA have evolved in different healthcare settings to meet differing needs. While none of these trials specifically examined HF patients, we know that HF is one of the commonest reasons for unscheduled medical admission3, so we feel these processes are relevant to our patients. However, subgroup analysis of primary outcomes in the Cochrane review showed the positive outcomes were primarily the result of CGA wards and the effect was not as clearly seen where patients remained in a general ward receiving assessment from a visiting specialist multidisciplinary team. This requires research specifically for HF patients but certainly raises an interesting debate for where these complex patients are most optimally managed.

Applying the Guidelines in Frail Older Adults with Multimorbidity

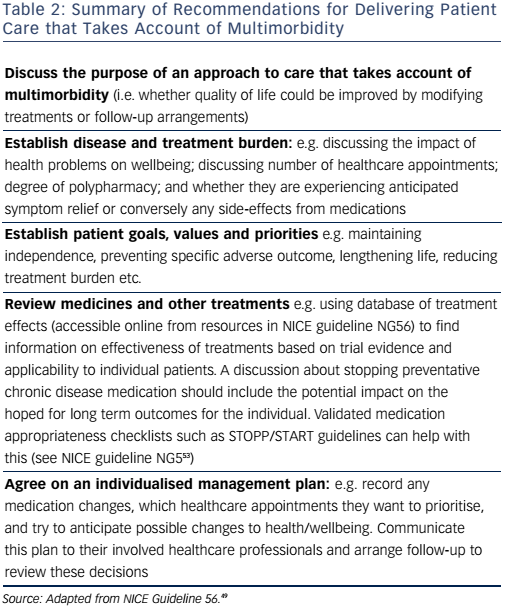

There is increasing recognition that disease-specific guidelines have traditionally failed to meet the complex needs of physically frail individuals with multimorbidity. Distinct therapeutic strategies that carefully balance the characteristics of frailty against the potential for benefit and harm from treatment need to be developed as well as consideration given to how services can be reorganised to facilitate such an approach. The recent ESC guidelines on heart failure have helpfully highlighted some of these issues, with a specific chapter devoted to comorbidities. More recently, the NICE have published excellent guidance for assessing and managing multimorbidity49 and Table 2 summarises their recommendations.

Palliative, Supportive and End-of-life Care

Care planning for HF patients should incorporate anticipatory care planning and end-of-life care. Patients with severe HF symptoms despite optimal treatment, who are having repeated hospitalisations or experiencing progressive functional decline and dependence, have much to gain from supportive and palliative care services. In our own clinical practice, we find asking ourselves the ‘surprise’ question (“would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year?”) valuable. This is known to be a reliable and valid tool to identify patients who have a greatly increased risk of mortality in the coming year.50

The majority of HF patients value quality of life over longevity.51 However, the transition from solely focusing on disease modification to prioritising quality of life will be at a different point for each patient. Advance care planning allows for open discussion of patients’ preferences in treatment and preferred place of care. Key aspects of the clinician’s role in advance care planning have been highlighted in the ESC’s 2016 guidelines1 and can be summarised as follows.

- Discuss when to stop medication that does not have an immediate effect on symptom management or health-related quality-of-life, e.g. statins or osteoporosis treatment

- Document patient’s decision regarding resuscitation attempts

- Discuss deactivation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator at end-of-life

- Discuss preferred place for care and death

- Offer emotional support to the patient and family and/or caregiver with appropriate referral for psychological or spiritual support

As symptoms and quality of life change over time, regular re-assessment is needed.

Assessing the level of cognitive impairment will determine how much advance care planning occurs with the patient directly; if there a concerns about cognitive abilities, it is important to check what powers of attorney are in place. For a more detailed review of the management of HF in patients nearing the end of life see LeMond and Goodlin.52

Conclusion

Given demographic changes, improved survival from coronary artery disease and an anticipated doubling in prevalence of HF over the next few decades, it is important that clinicians develop a better understanding of the complex interactions between heart failure and old age.

More research is required to evaluate the effectiveness of standard HF management among older adults, and also in the subgroup that requires nursing home care. Clinicians managing HF need to have an increased understanding of the complex interplay of multimorbidity, frailty and cognitive impairment because these domains are significant determinants of a patient’s place and level of care. We hope that by highlighting some of these special considerations, we can start to think practically about the best ways to tailor individual patient care.