Heart failure (HF) is associated with poor quality of life, high risk of death and is the leading cause of hospitalisation.1 With an ageing population and improved care for cardiovascular diseases, the prevalence of HF is increasing. Despite advances in HF therapies, 1–10% of the population with HF progress to an advanced stage of the disease.2,3 In the US, an estimated 250,000–300,000 patients younger than 75 years suffer from advanced HF; extrapolated, this would yield approximately 500,000 patients in the EU.4 Prognosis in advanced heart failure is poor, with 1-year mortality rates of 25–50%5,6

Heart transplantation (HTx) remains the gold standard treatment for severe HF refractory to medical and device therapy, with a 1-year survival of almost 90%.7,8 However, since access to organs is limited, durable left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are increasingly being implanted in these patients either as bridge to transplantation or destination therapy.9

There have been remarkable advances in mechanical assist device therapy over the past decade and current data indicate a survival after LVAD implantation of around 80% at 1 year and 70% at 2 years.10,11 Patients are, however, believed to be underserved regarding advanced HF therapies.12,13 While the main explanation for HTx is organ shortage, important reasons for underuse of LVADs are most likely a lack of awareness among clinicians caring for patients with HF and difficulty in assessing the need for advanced therapy.

Accurate prognostication in HF is challenging. The transition from stable, chronic HF to advanced HF is often gradual and no single test or imaging modality is capable of identifying this change in severity. For general practitioners or cardiologists who do not deal with advanced HF on a daily basis, it is difficult to identify patients who may benefit from HTx or LVAD therapy. Patients are often referred too late, when end-stage organ failure that disqualifies them for advanced treatment is already present.14 While HF teams and advanced HF referral centres follow rigorous selection criteria and guidelines when selecting patients for HTx and LVAD implantation, there are no guidelines or criteria to serve the GP or cardiologist in deciding when to refer patients for advanced HF assessment and potential selection for advanced therapy.15–17

Referral to an Advanced Heart Failure Centre

Before advanced therapy is considered, evidence-based HF therapy should be optimised. Medication must be uptitrated to maximum tolerated doses and patients should receive cardiac resynchronisation therapy and/or implantable defibrillation therapy (ICD) as indicated according to current guidelines.18

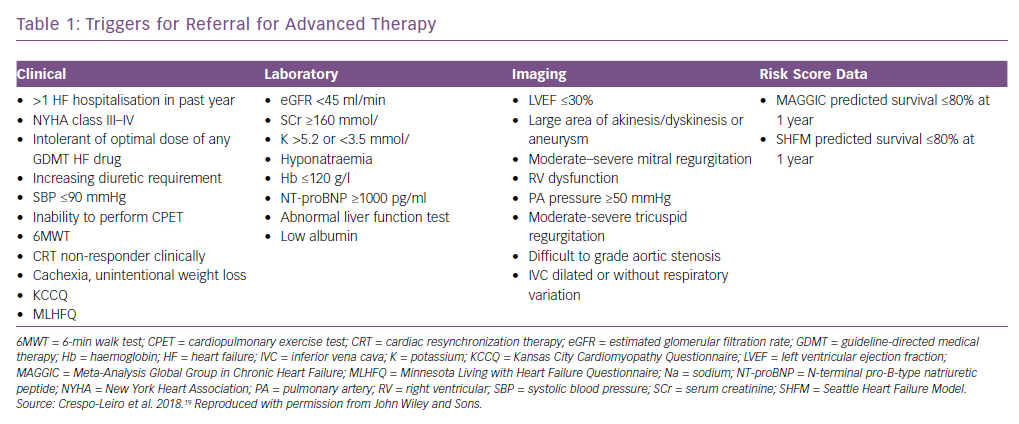

No validated criteria or cut-off values for referral to an advanced HF clinic or HF specialist exist. The Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology position statement lists triggers for referral (Table 1).19 The variables listed include clinical, laboratory, imaging and risk score data; they are all relevant prognostic variables, but many are non-specific and/or subjective. The variables should perhaps be seen as general markers of deterioration rather than distinct referral criteria.

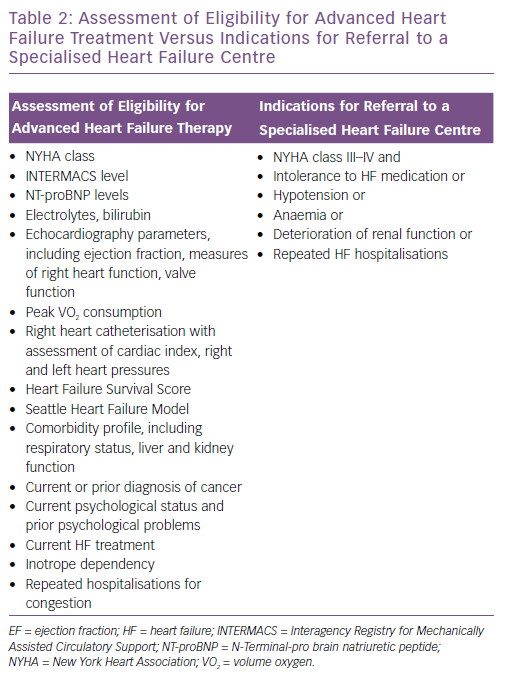

Articles in which referral for advanced HF therapy is discussed tend to focus on selection criteria for HTx or LVAD implantation rather than referral criteria.14 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, 6-minute-walk test, assessment of prognosis using comprehensive risk scores, evaluation of end-stage organ failure, assessment of cardiac index and intracardiac pressures measured by right heart catheterisation are all part of a complete patient eligibility assessment performed by the interdisciplinary HF team at specialised HF centres when evaluating potential candidates for advanced HF treatment.20 It should be noted that, for referral to a HF centre, a complete assessment of the patient is not required. The general cardiologist or primary care physician does need, however, to identify that the disease is progressing toward a stage of advanced HF, and this may be challenging.

Systematic screening of certain patient categories has been suggested as a way of improving referral for advanced therapy. A pilot study suggested that screening patients receiving cardiac resynchronisation therapy for possible HTx or LVAD indication identified otherwise neglected candidates.21. The Screening for Advanced Heart Failure Treatment (SEE-HF) study showed that actively screening patients with cardiac resynchronisation therapy and/or an ICD in an outpatient setting found few patients were candidates for advanced therapy. However, when selecting patients with an ejection fraction (EF) <40% and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III–IV, 26% were found to have an unrecognised need for advanced therapy (HTx and/or LVAD).22 More studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of screening to identify candidates for advanced therapy.

Clinical decision supports (CDS) may be of value in identifying patients eligible for advanced therapies. Evans, et al. developed a computer application that, by automatically extracting information from the patient’s integrated electronic health record, could monitor their HF status and alert the treating physician if the criteria for advanced HF were met.23 More patients were referred to specialised heart facilities when CDS were used than in the year before CDS were introduced. However, if information cannot be abstracted automatically – which is the case in many healthcare systems – it would be time consuming to use the application and possibly of less help in busy daily practice.

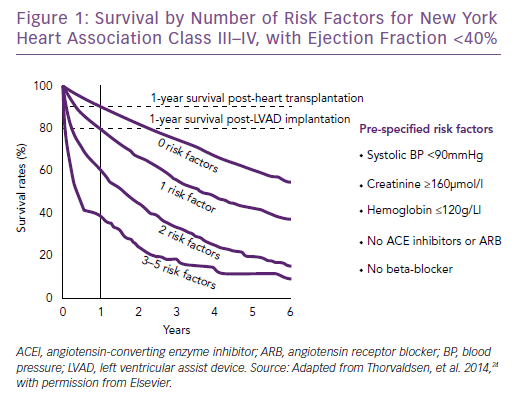

Most likely, simpler tools are needed to ensure timely referral. In a study by the Swedish Heart Failure Registry, five risk factors were suggested as triggers for referral to an advanced HF centre.24 For patients with NYHA class III–IV HF and EF <40% with one or more of the defined risk factors present, 1-year survival was worse than for HF patients post-HTx or post-LVAD implantation (Figure 1). One or more risk factors is therefore reason to refer to a HF centre. The five risk factors were: systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg; creatinine >160 µmol/l, haemoglobin <120 g/l; no renin-angiotensin system antagonist and no beta-blocker. These risk factors are easily identified in daily clinical practice and reflect disease severity. The focus of the study was not on optimal biological discrimination (in which glomerular filtration rate rather than creatinine would be used, and discrimination would be formally assessed with e.g. areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves), but rather on simple, memorable and distinct criteria suitable for busy clinicians. In a recent review article, it was suggested that if a patient was highly symptomatic (NYHA III–IV) despite optimal HF treatment, this should prompt for referral to a HF centre.4 More than one hospitalisation despite good medical therapy indicates disease is severe, as do intolerance to HF medication and hyponatremia.12,25

A pragmatic approach, such as using the five risk factors or a patient being highly symptomatic despite the best care as referral criteria could increase the number of referrals. By no means does this imply that the majority of these patients would benefit from or be eligible for HTx or LVAD implantation; it means only that they deserve at least one expert assessment by a HF specialist. Additionally, underuse of intermediate-level HF interventions such as cardiac resynchronisation and ICD therapy has been reported previously, so a more liberal referral to a HF specialist seems motivated by a wish to optimise evidence-based treatments.26–28

Palliative programmes have been shown to reduce readmissions and improve symptoms in patients with end-stage HF.29 However, palliative care is substantially less implemented for patients with HF than in those with cancer, and is often initiated too late.30,31 The benefits of palliative care have been recognised by the American Heart Association and the body of literature focusing on the integration of palliative care in HF management is increasing.32 Therefore, even for patients with a heavy comorbidity burden or those who are presumed to be too old for advanced HF therapy, a referral to an advanced HF centre is justified for considering different treatment options and initiating palliative care if appropriate.

Table 2 shows the important differences between the comprehensive assessment of a potential candidate for LVAD and/or HTx and suggested criteria for referring a patient to an advanced HF centre discussed in this article.

Conclusion

Mortality in advanced HF remains high. Identifying patients in need of advanced therapy starts with referral to a heart failure centre. Timely referral for evaluation for HTx and LVAD therapy is crucial for the success of these treatments. In contrast to the complex criteria for selection for LVAD and HTx therapy, indication for evaluation to a HF specialist should simply be deterioration despite optimal HF care.