Heart failure (HF) is estimated to affect 26 million people worldwide and is responsible for an annual global economic burden of US$108 billion.1,2 An ageing population and a reduction in mortality from other conditions such as acute MI are expected to result in an increased HF prevalence throughout much of the world.1,3–6 The prevalence of HF has particularly increased among those aged 85 years and older.7,8 HF is an especially burdensome disease both physically and psychosocially. Compared with those with other chronic illnesses, patients with HF have significantly more impairment in quality of life.9 According to the WHO, nearly 39% of adults needing palliative care at the end of life have cardiovascular disease.10 Exacerbations in symptoms and carers being unprepared for this are likely to contribute to HF being a leading cause of hospital readmissions.11–13 Hospice care can ameliorate distress at the end of life for patients with HF, yet it is underused in this population.14–17 Increasing the use of hospice care among this population should be a priority, although determining when a patient with HF should be referred to hospice care remains a challenge. In this paper we discuss the benefits of hospice care for people with HF, detail the factors contributing to the underuse of hospices among people with HF and offer recommendations to optimise hospice use.

Benefits of Hospice Care for Patients with Heart Failure

Hospice care is team-based palliative care typically reserved for those with a life expectancy of 6 months or less. It can be provided to any patient with a life-limiting illness and combines medical care, pain management and emotional and spiritual support. While palliative care may be received alongside disease-directed treatment, hospice care focuses on comfort and quality of life when a cure is no longer possible. It is the model for high-quality patient-centred care for those facing a life-limiting illness.18 Hospice care is typically provided in the place where a patient lives – whether their own home or in a care home or nursing home. Many countries also have inpatient hospice facilities that may be free-standing or located in a hospital; however, the structure of these services differs between countries. Patients receiving hospice care generally experience lower rates of hospitalisation, admission to intensive care and invasive procedures at the end of life.19 Additionally, hospice care often improves symptom distress, care quality, caregiver outcomes and patient and family satisfaction.20–24 Some researchers have found that hospice and palliative care is associated with longer survival in some HF patients.14,19,22,25

In the US, roughly one in four Medicare beneficiaries hospitalised for decompensated HF are readmitted within 30 days of discharge.26 Preventable hospital readmissions are estimated to cost the US healthcare system US$25 billion each year and place patients at greater risk of complications and infections.27 Similar rates of hospital readmissions with a similar burden have also been documented around the world.28,29 Four in 10 patients with HF in Greece were readmitted to hospital in less than a year, according to one study.30 Inadequate follow-up care is a major factor in hospital readmissions and hospice use has been associated with a lower risk of 30-day hospital readmission among patients with HF.31 Another line of research shows that hospice care leads to reduced medical costs while providing these well-established benefits for seriously ill patients.19,22,25,31 Although most research on the cost-effectiveness of hospice care has been conducted in the US, reduced costs from hospice use have also been documented in Israel. 32

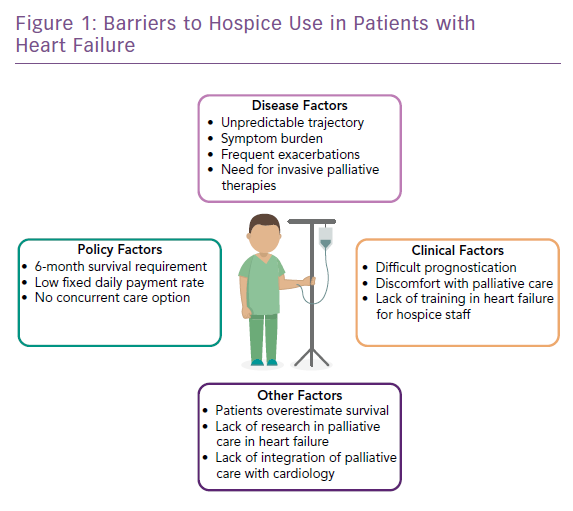

Contributing Factors to Hospice Underuse in People with Heart Failure

Despite the benefits of hospice care, patients face significant barriers to receiving timely referrals. In the UK, only 4% of patients with HF have received care from a hospice or palliative care team.33 Nearly one-third of American patients with HF receive hospice care at the time of death and those who do tend to enrol late in the course of their disease.34–37 In one study of hospitalised patients with HF, those discharged to hospice care had a median survival of 11 days and nearly one-quarter of patients died within 3 days.34 The short length of stay in hospices for many patients with HF is especially concerning, as this suggests that patients and their families may not receive the full benefit of the care. Multiple studies have found an association between family perception of a late referral to hospice and a poorer care experience for patients and family members.21,38–40 Patients with short lengths of stay in hospices are also less likely to receive care at home despite this being the preference of many.41,42 We have identified seven major themes that drive hospice underuse in HF.

Disease Trajectory

Despite the benefits of hospice care, patients face significant barriers to receiving timely referrals to that care stemming from the unique course of HF and the difficulty there is in providing an accurate prognosis (Figure 1). Patients with HF tend to experience a gradual decline punctuated by intermittent exacerbations that, when treated, can result in a near return to the patient’s pre-exacerbation status.43,44 As it is not possible to know which exacerbation will be fatal, death often seems unexpected.45 The fact that a patient’s prognosis is the predominant criterion used to indicate eligibility for hospice care makes it difficult to know when it is appropriate for patients with HF to be referred.46 Patients who experience a more rapid decline may better recognise their limited life expectancy and be more willing to shift from conventional to palliative care and be motivated to seek additional support.47–49 Advance care planning (ACP), which has been associated with increased hospice use, is critical given HF’s undulating disease course; however, most patients with HF lack advance directives.50,51 There is growing acceptance that provision of palliative care should be based on patient need and be given at any point in a patient’s illness, however, the disease trajectory of HF remains a barrier to hospice use by this population.

Symptom Burden that is Difficult to Manage at Home

Some patients with HF experience more severe symptoms than patients with advanced cancer.52,53 Dyspnoea, fatigue and pain are particularly problematic and are likely to contribute to the higher rate of acute medical service use in the last 30 days before death among patients with HF compared with those with cancer.46,54,56 As a result, patients with HF have higher rates of hospital death compared with patients with other diseases.57 Depression is also highly prevalent among patients with HF.58

The high symptom severity of HF also contributes to caregiver burden. As patients with HF become unable to handle activities of daily living, carers – who are usually family members – provide vital support and care. These activities may include monitoring of wellbeing and changes in health status, supporting adherence to dietary restrictions, managing medication that frequently requires modification, ensuring safety and providing emotional support.59 As patients decline, carers increasingly provide more hands-on personal care such as dressing and bathing. Relatives and carers of patients with HF report high rates of depression and impaired qualify of life.60,61 Carers often lack clinical knowledge of the condition and its management and many feel unprepared to deal with exacerbations at home.62-64 According to one Swedish study, nearly one-third of partners of patients with HF reported perceiving a medium level of carer burden.65 Unpaid carers represent a ‘hidden’ lay palliative care workforce who are vulnerable, underserved and in great need of professional palliative care support.66

Geographic and Socioeconomic Disparities

Social and cultural factors influence how care is used at the end of life. HF is a care-intensive disease and hospice care is unable to be given around the clock. Patients who lack familial carers or the money to pay carers may be less able to remain at home with hospice care. Median income has been inversely associated with lower odds of 30-day hospital readmission, suggesting that financial resources are essential for remaining at home.67 Multiple studies have found an association between low socioeconomic status and more aggressive medical care at the end of life, increased likelihood of dying in institutional settings and a lower likelihood of receiving hospice services.68–70

In many European countries, palliative care is funded through a mix of statutory funding, charities, private insurance and out-of-pocket payments.71 A high reliance on charitable giving results in a postcode lottery, with available services being determined by where one lives. Inpatient hospices are particularly reliant upon charitable income to cover costs. It is perhaps unsurprising then that inpatient hospice deaths in England are less likely in more deprived areas.72 Rural patients have poorer access to hospice and hospices in rural areas may be more likely to serve a smaller number of patients and to limit expensive services due to fear of financial risk.16,73,74

Late Referrals to Palliative Care and Hospice

The European Society of Cardiology, American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) have called for palliative care to be integrated into the care of patients with advanced heart disease, yet patients with HF are often not referred to palliative care.75,76 A survey of Japanese Circulation Society-authorised cardiology training hospitals found that 42% of institutions had held a palliative care conference for patients with HF, but only 9% held them regularly.77 Sixty-one percent of surveyed hospitals reported rarely holding them.78 A study of people who had died in Veterans Affairs health facilities in the US found that less than half of those with cardiopulmonary failure received palliative care consultations.79 Another study involving 215 patients with either advanced cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or HF found that when a physician discussed hospice care there was a strong association with subsequent enrollment, however, only 7% of patients with HF enrolled compared with 46% of patients with cancer.80 In general, palliative care should be considered from diagnosis onward; however, it may be unwarranted for cardiologists to refer to palliative care specialists in early-stage HF as patients may be asymptomatic or sufficiently cared for with primary palliative care from their HF clinician.81,82

Patients with HF who may appear to be near death are often candidates for procedures such as left ventricular assist device or heart transplant. Hospice eligibility is less clear-cut for people with HF and may complicate referrals. Inaccuracy in HF prognostication is another impediment to palliative care and hospice referral. One study of physicians found that fewer than half of physicians accurately estimated survival in patients with HF.83

Palliative care needs assessments tools for HF, such as the Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease–Heart Failure (NAT:PD-HF), have been validated and tested internationally.84,85 Although needs assessment tools may assist in the identification of palliative care needs for people with HF, a recent test of the feasibility of a Dutch NAT:PD-HF suggests that an instrument alone is likely to be unable to facilitate timely recognition of palliative care needs by professionals with limited palliative care training and expertise.85

Professional Factors

Documentation of advance directives has been associated with lower costs, lower risk of in-hospital death, and greater hospice use in regions with higher levels of end of life spending; however, most hospitalised patients with HF do not have documented advance directives.50,86

Cardiologists have reported discomfort in discussing end of life care and many differ in their beliefs regarding whose responsibility these conversations are.87 Physicians also report feeling more uncomfortable discussing palliative care with people with HF than with patients who have lung cancer.83 Many cardiologists have also reported that time constraints are a barrier to their engagement in ACP.

Advances in therapies and devices for the treatment of HF may complicate the work of hospice providers. Few hospices have training, policies or procedures or standardised care plans for managing patients with HF.16 Although one-third of Medicare patients with ICDs receive hospice care, most hospices lack protocols for ICD deactivation.88,89 In a UK study of palliative care professionals, 24% reported experiencing difficulties with ICD deactivation at the end of life and 83% of respondents reported ICD deactivation was seldom discussed by cardiologists before making a palliative care referral.90 ICDs do not improve symptoms and device discharge or complications may add to patient suffering.46 In addition to the prohibitive costs of inotropes and other IV drugs, many hospices will not provide IV treatments in the home setting. Hospices may not provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines despite the fact that sleep-disordered breathing occurs in at least half of people with advanced HF.16,91

Many hospices lack the knowledge and expertise necessary for the management of HF. A study of hospice staff in North and South Carolina in the US found that most staff lacked experience and were uncomfortable when using inotropes, mainly because their hospice did not provide coverage of inotropes.92 In a focus group of HF palliative care specialist nurses in Scotland and England, junior nurses reported their reluctance to accept patients with HF for hospice care and some hospices needed reassurance about their ability to meet the needs of patients with HF.93

Recommendations

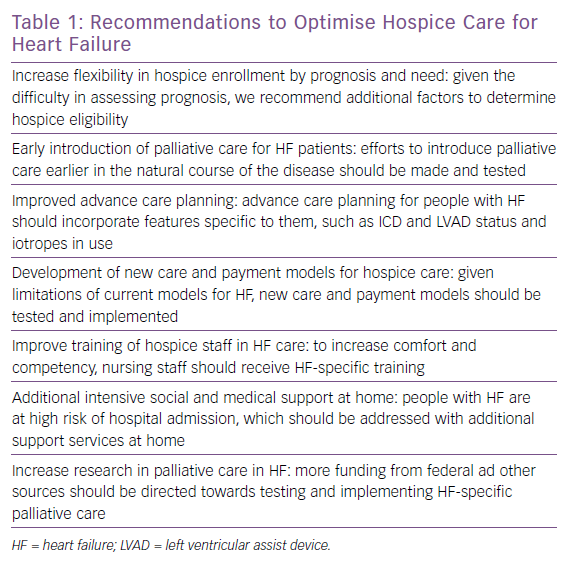

Improved Advance Care Planning and Earlier Palliative Care Integration

Patients with HF and often their clinicians rarely realise the terminal nature of their disease.94 Little is known about communication and decision-making between clinicians and patients with HF, yet patient-centered communication is possible and essential.95 Clinicians must assist patients in developing a realistic assessment of their expected survival throughout the course of the disease that could assist decision-making related to advance care planning (Table 1).96 Given the shortage of palliative care specialists, cardiologists must become proficient in generalist palliative care skills.97 Experts recommend that palliative care be introduced into HF care by patients’ primary clinical teams, followed by palliative care consultation in selected patients.96

The ESC recommends that end of life care be considered for people with HF who:

- Have progressive functional decline and dependence in most activities of daily living;

- Experience severe HF symptoms with poor quality of life despite optimal pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies;

- Have frequent hospital admissions or other serious episodes of decompensation despite optimal treatment;

- Have been ruled out of heart transplantation and mechanical circulatory support;

- Patients experiencing cardiac cachexia; and

- Those clinically judged to be near the end of life.98

Creative partnerships and collaboration between teams may be tailored to take advantage of the staffing and resources of particular healthcare systems and facilities. One Canadian institution found that embedding a palliative care team into the HF team resulted in a significant increase in ACP documentation, a decrease in the use of emergency department visits and hospital readmissions, and high patient and family satisfaction.78 St Luke’s Hospice in England partnered with local NHS trusts to improve the management of care for patients with advanced HF. After the adoption of a trigger tool to identify patients who could benefit from palliative care, access to advance care planning and deaths outside the hospital increased.99

Increased Research into Palliative Care and Hospice in Heart Failure

Insufficient funding for palliative care research has contributed to an inadequate evidence base for improving symptom management, communication skills, care coordination, and the development of care models.100 Less than 0.2% of the annual budget of the National Institutes of Health in the US has been spent on palliative care research.101,102 After the recognition of palliative care as a medical specialty, there has been an increase in palliative care research, however, a concerted effort to increase the evidence base in this field is needed.103 Most of the funding for palliative care research has been focused on oncology, resulting in limited funding sources for research into palliative care for people with HF.104,105 Chart reviews have indicated that only about 10% of patients with HF receive palliative care consultations and these tend to occur in the last month of life.106 Despite being the leading cause of death in the US, fewer than 19% of Medicare patients who died while receiving hospice care had a cardiac or cardiovascular diagnosis.18,107 Improving the evidence base is essential for the advancement of specialist palliative care and hospice use in HF.

Development of New Models of Hospice Care

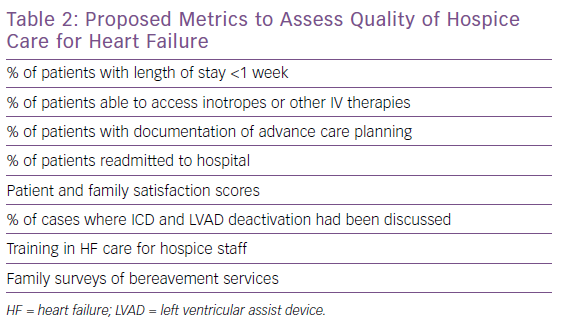

Innovative home-based programmes for HF management have been shown to reduce hospital readmissions, reduce costs and improve quality of life.108 It follows that hospice care may better meet the needs of patients with HF were hospice services designed with HP needs in mind. Indeed, research suggests that a hospice model tailored to the needs of patients with HF might improve enrollment among this population.14 Particular metrics are needed to assess the quality of hospice care for patients with HF (Table 2).

Hospice staff must also be sufficiently trained to manage the needs of patients with HF. In response to the recognition of unmet palliative and end of life care needs among patients with HF, the British Heart Foundation funded HF nurses to receive training in palliative care and advanced communication skills. An evaluation of the programme indicated that patients and their carers reported improved service quality, better care coordination, reduced anxiety and improved ability to cope with illness and death.93

Being willing to forgo life-sustaining treatment does not identify patients with a greater need for hospice services and, therefore, hospice fails a test of fairness.109 In the US, other Medicare benefits are not subject to cost-based restrictions, rather they are determined by a medical need for diagnosis and treatment of an illness or injury and made through an evidence-based process.110 Advocates are pushing for a concurrent care model in which patients may receive supportive care services typically provided by a hospice while continuing to receive curative treatment. Hospice criteria based on patient need and functional status should be established.109,111

Australia uses a payment model for palliative care based on patient characteristics, with reimbursement determined by the patient’s performance status, phase of illness, care setting and age. Similar models are also being explored in England and Switzerland.71 Cardiology should join palliative care in advocating for the creation of new models of end of life care for patients with HF – including features that meet the unique physical and psychosocial needs of those with HF.

Conclusion

Underuse of hospice care for people with HF is a significant public health problem. Despite differing social issues and healthcare systems, barriers to hospice use for patients with HF are remarkably similar in high-income countries. The increasing prevalence of HF demands improvements in how we meet the needs of patients nearing the end of life and their carers. With a growing shortage in the palliative care workforce, it is imperative that cardiologists develop comfort and proficiency in ACP and primary palliative care.112,113 Without patient-centred and disease-specific modifications, it is unlikely that hospice use will increase among patients with HF. Improving communication and developing trust must be priorities in improving end of life care for all. Innovative programmes and models of care may extend the reach of palliative and hospice care in institutions and in more remote geographic areas. Despite the challenges, there are actions we can take to increase hospice use among patients with HF.