Acute heart failure (AHF) presents symptoms primarily the result of pulmonary congestion due to elevated left ventricular (LV) filling pressures with or without reduced ejection fraction (EF). Common precipitating pathology includes coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension and valvular heart diseases, in addition to other noncardiac conditions, such as diabetes, anaemia and kidney dysfunction.1,2 Additionally, AHF poses major medical and socioeconomic burdens. It represents the most common discharge diagnosis in patients over 65 years of age in the US, and an AHF patient that requires hospitalisation has a 90-day mortality approaching 10 %.3,4

The cornerstone of AHF treatment is diuretics and vasodilators, such as nitrates. Due to a lack of randomised controlled trials, the use of nitrates for management of AHF is not universally adopted. While organic nitrates are among the oldest treatments for chronic stable angina, they are underutilised in AHF. Organic nitrates are available as sublingual tablets, capsules, sprays, patches, ointments or intravenous (IV) solutions, all of which are potent vasodilators. Because of the challenges in AHF research, a data imbalance between acute and chronic HF treatment exists as more studies have been performed in the latter. Thus, the current level of evidence for the use of nitrates in AHF is only rated as 1C, i.e., ‘expert opinion’.5,6 The purpose of this article is to review the clinical efficacy and safety data of nitrates in AHF.

How Nitrate Works

Mechanism of Action

Nitrate-induced vasodilatation starts at cellular level by the activation of the enzyme soluble guanylyl cyclase on nitrate-derived nitric oxide (NO), leading to increased bioavailability of cyclic guanosine-3′,-5′- monophosphate (cGMP) and activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Downstream vasodilation resulting from these processes requires reduction of intracellular calcium levels by decreasing calcium exit from the cytoplasmic reticulum and reducing its influx from the extracellular space. The decrease in intracellular calcium leads to venous and arterial vasodilation.7,8 More recent studies suggest epigenetic regulation of nitrate-induced smooth muscle relaxation where nitroglycerin may increase histone acetylase activity, and N-lysine acetylation of contractile proteins that may then influence nitroglycerin-dependent vascular responses.9,10

Applied to the patient with congestive HF, vasodilatation induces a substantial reduction in biventricular filling pressure. Moreover, it reduces systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance and systemic arterial blood pressure (BP),11 all of which lead to modest increases in cardiac stroke volume and cardiac output.12

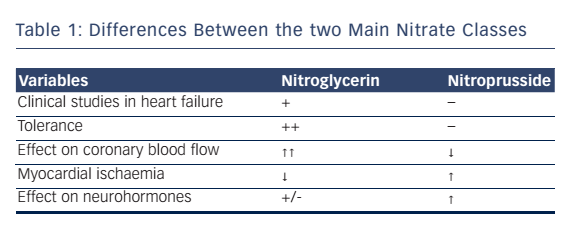

Overall, the two most commonly used IV NO sources used clinically in the setting of AHF is the organic nitrate donor nitroglycerin, and the inorganic nitrate source sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Nitroglycerin potently dilates large arteries (including coronary arteries) but has less effect on smaller arterioles, while SNP is a predominant arteriolar dilator. That makes SNP is effective in recompensating patients with AHF.13 Other important clinical differences between organic and inorganic nitrates are summarised in Table 1.14

Do Nitrates Have any Effect on Acute Heart Failure?

Several studies have suggested that nitrates are ineffective in AHF. The Vasodilatation in the Management of Acute Congestive Heart Failure (VMAC) study was a randomized, controlled AHF trial comparing nesiritide (the recombinant B-type natriuretic peptide) in 204 patients receiving either nitroglycerin (n=143) or placebo (n=142). While this study demonstrated that nitrates are not extremely effective in improving haemodynamics or AHF symptoms, the major criticism is that they tested low, but commonly used, IV nitroglycerin doses, i.e. 30–60 μg/minute.15 In fact, Corstiaan et al., suggested that the 13 μg/ minute median dose of nitroglycerin used in VMAC was too low to improve global haemodynamic parameters. This was demonstrated by the absolute lack of any benefit on haemodynamic parameters between the nitroglycerin-treated patients and those in the placebo arm.16 Similarly, Beltrame et al. in a study evaluating ventilatory parameters in 69 AHF patients, compared 2.5 to 10 mcg/minute of nitroglycerin to morphine and furosemide and found no differences.17 These studies suggest that there is no acute clinical benefit from lowdose nitroglycerin in AHF.

In 2015, Turner et al. published a 634 patient systematic review to evaluate the effect, safety and tolerability of IV nitrates in AHF. After searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE and EMBASE, they found only four randomised controlled trials that met the inclusion criteria of comparing nitrates (isosorbide dinitrate and nitroglycerin) with alternative interventions (furosemide and morphine, furosemide alone, hydralazine, prenalterol, IV nesiritide and placebo) in the management of AHF with a primary outcome of rapidity of symptom relief. The authors stated that there was no difference between nitrate therapy and alternative interventions in regard to symptom relief and haemodynamic variables. However, they also concluded that nitrates were associated with a lower incidence of adverse effects after 3 hours versus placebo, suggesting that the dose may have been inadequate. Ultimately, this systematic review could not draw a firm recommendation or a conclusion as to the optimal therapy given the limitations of such a small number of adequately powered studies.18

Are High-dose Nitrates Effective?

Investigators have addressed the dose-response relationship for the use of nitroglycerin in AHF. In a recent review, Corstiaan et al, proposed the more aggressive use of nitrates and a more conservative use of inotropes in AHF patients with normal or high BP. The dose of nitrates they reported as associated with favorable effects was at least 33 μg/ minute or higher.16

The above conclusions are supported by a number of smaller sized interventions. In a pilot study, Breidthardt et al., randomised 128 AHF patients to standard therapy with or without high-dose sublingual and transdermal nitrates. The median nitrate dose during the first 48 hours in the high-dose group was 82.4 mg versus 20 mg in the standard therapy group, and the primary endpoint was cardiac recovery, as quantified by B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels, in the first 48 hours. Although mean BNP levels decreased in all patients, the decrease was larger in the high-dose nitrate cohort, with most of the decrease in BNP already apparent within 12 hours (decreased by an average of 29±4.9 versus 15±5.4 % in the high- and low-dose groups, respectively; P<0.0001). They concluded that adding a high-dose nitrate strategy to standard therapy accelerates cardiac recovery and was a notably safe strategy. Although this study randomised a small number of patients, its baseline characteristics, treatment and in-hospital mortality rates were similar to those reported by large registries.19

Similarly, in an open label, non-randomised trial, Levy et al. studied the effect of high-dose nitroglycerin in severely hypertensive decompensated HF patients. Nitroglycerin dosing consisted of 2,000 mcg every 3 minutes, to a maximum of 20,000 mcg. They foundthigher doses were more effective at decreasing intubation (13.8 versus 26.7 %) and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (37.9 versus 80.0 %) compared with non-high-dose nitroglycerin. In the high-dose group, a rapid and profound decrease in BP occurred, but without an associated increase in adverse events.20

Finally, an ICU study of 40 severe AHF patients showed benefit from higher-dose nitrates. Patients were randomised to receive either low-dose IV furosemide (40 mg) and high-dose IV isosorbide dinitrate (3,000 mcg) every 5 minutes, or 1 mg/hour of isosorbide dinitrite (ISDN) that was increased every 10 minutes by 1 mg/hour with and high-dose IV furosemide bolus 80 mg repeated every 15 minutes. They reported high-dose nitrate patients had fewer intubations (20 versus 80 %; P<0.0004), higher oxygenation at 1 hour (96 versus 89 %; P<0.017) and a lower rate of the combined endpoint of death, MI and endotracheal intubation (25 versus 85 %; P<0.0003).21

The studies reviewed in the two sections above suggest that while low-dose nitroglycerin may offer minimal clinically detectable benefit in AHF, higher dose nitroglycerin may provide significant advantages over standard therapy. Also of import is that the rates of adverse events in hypertensive AHF patients receiving high-dose nitrates appear to be low.

Do Nitrates Improve Mortality and Endotracheal Intubation Rates?

Like Sharon et al.,21 Cotter et al. evaluated high-dose nitrates in 110 AHF patients. They randomised patients into two groups: (1) high-dose ISDN (3 mg bolus every 5 minutes) and low-dose furosemide (40 mg IV bolus single dose); (2) low-dose ISDN (1 mg/hour ISDN, increased every 10 minutes by 1 mg/hour) and high-dose IV furosemide (80 mg IV bolus every 15 minutes). They reported that only 20 % of the highdose nitrate cohort required mechanical ventilation versus 80 % in the low-dose group (P<0.001). In addition, the high-dose ISDN group had a more rapid increase in arterial oxygen saturation.22

Other studies have demonstrated potentially beneficial mortality effects with nitrates as well. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) reported, in a propensity scorematched data analysis of hospitalised AHF patients, that those treated with inotropes (dobutamine, dopamine or milrinone) suffered higher mortality than those treated with vasodilators. The authors suggested a benefit of vasodilator therapy on reducing in hospital mortality.23 Using the ADHERE Registry, Peacock et al. demonstrated that early vasoactive initiation is associated with improved outcomes in patients hospitalised for AHF. They examined the relationship between vasoactive time and inpatient mortality within 48 hours of hospitalisation. Vasoactive agents were used early (defined as <6 hours) in 22,788 (63.8 %) patients and late in 12,912 (36.2 %). Median vasoactive time was 1.7 and 14.7 hours in the early and late groups, respectively. In-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the early group (odds ratio, 0.87; 95 % CI [0.79–0.96]; P=0.006), and the adjusted odds of death increased 6.8 % for every 6 hours of treatment delay (95 % CI [4.2–9.6]; P<0.0001).24

Finally, Aziz et al. evaluated outcomes in 430 AHF patients receiving diuretics alone (furosemide mean dose is 59 mg), nitroglycerin plus diuretics (nitroglycerin range doses are 5–15 mcg/minute; furosemide mean dose is 75 mg), or neither. They reported 24-month mortality was lower with nitroglycerin plus diuretics (13 %), than either diuretics alone (18 %) or neither (21 %; P=0.002). Of note, all treatments were initiated in the emergency department.25

Potential Mechanism for the Beneficial Effects of Nitrates

The exact mechanism for clinical improvement with nitrates is not clearly defined; however, a number of investigators have proposed potential mechanisms. Corstiaan et al., was the first study demonstrating that the nitroglycerin increases the number of patent capillaries in patients with AHF. In this investigation nitroglycerin was given as an IV infusion at a fixed dose of 33 mcg/minute. Using sidestream dark field imaging, sublingual microvascular perfusion was evaluated. They concluded that impaired microcirculation can be improved by the use of a lower dose IV nitroglycerin infusion.16

Another potential mechanism for improved outcomes with nitrates in AHD is the hypothesis that nitrates may improve myocardial stress. This is reflected in a number of natriuretic peptide studies that have reported decreased BNP levels after initiation of nitrate therapy.19,26 Further, Chow et al. randomised 89 AHF patients to either nesiritide or nitroglycerin. They reported significant reductions in N-terminal proBNP and BNP levels with similar clinical and haemodynamic improvements.27 In this study, both treatments did not have statistically significant effects on morbidity or mortality in this high-risk group of patients.

Finally, vasodilators in general – and nitrates in particular – may provide improved short-term clinical outcomes due to their ability to provide rapid haemodynamic benefits. This is due to their vasodilatory effect that may induce a substantial reduction in right and LV filling pressures, decrease systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance, as well as lower systolic BP (SBP). Ultimately this leads to a downward shift of the ventricular pressure and volume relationship, such that the same volume has lower filling pressures, and myocardial efficiency improves.

Current Practice and Recommendations

When not to use Nitrates

The current American Heart Association guidelines recommend the use of a vasodilator, e.g., nitrates, in addition to diuretics in patients who do not respond to diuretics alone, and in those with evidence of severe fluid overload in the absence of systemic arterial hypotension (class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C).6,28 Alternatively, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends the use of nitrates as a continuous infusion in patients with SBP >110 mmHg, and to be used with caution in patients with SBP between 90 and 110 mmHg (class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).29

While nitrates have been used in AHF for many years, the lack of well-powered studies to support their use has lead to large practice variations. In fact, data from the EuroHeart Failure survey showed that in some regions of Europe nitrates are given to 70 % of patients presenting with AHF versus as little as 6 % in other regions.30 Similar findings were reported from the US ADHERE registry.23 Similarly, the Heart Failure Association of the ESC, the European Society of Emergency Medicine and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine published a recommendation on pre-hospital and early hospital management of AHF. They recommended that when SBP is normal to high (>110 mmHg), IV vasodilator therapy might be given for symptomatic relief as an initial therapy. Alternatively, sublingual nitrates may be considered.31

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society Heart Failure updated their management guidelines for AHF in 2012 as the following:

We recommend the following intravenous vasodilators, titrated to SBP >100 mmHg, for relief of dyspnea in haemodynamically stable patients (SBP >100 mmHg):

- Nitroglycerin (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence);

- Nesiritide (weak recommendation, high-quality evidence);

- Nitroprusside (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).32

Like all vasodilators, nitrates are contraindicated in the setting of hypotension, as well as in LV outflow tract obstruction, and in AHF mimics (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) where vasodilation is unlikely to provide a benefit. Furthermore, nitrates may result in excessive hypotension if there is concurrent vascular obstruction as occurs in pulmonary embolus. They should be used with caution in patients whom are preload dependent, and never in patients who are on phosphodiesterase inhibitors (i.e., sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenfil, etc.).

Challenges to Current Guidelines

Treatment algorithms suggested by recent ESC guidelines recommend the administration of diuretics to all patients with congestion and the addition of vasodilators (e.g., IV nitrates) if SBP is >110 mmHg. Despite this, the range of patients receiving concurrent vasodilator therapy is large. In a retrospective, observational study from the ESC-HF LongTerm Registry, 211 cardiology centres from 21 ESC member countries enrolled 12,440 patients (40.5 % with AHF) between 2011 and 2013. They found only 6.8 % of patients with a SBP >110 mmHg received vasodilators. Overall, treatment with IV nitrates is not adherent to guideline recommendations, and the authors suggest the variation in clinical practice may be the result of a lack of large randomised controlled trial evidence.33

The lack of quality research to support guidelines has been discussed by others: Cotter et al., in 2014, stated “despite a generation of clinical research we continue to treat patients with AHF with iv therapies during the first days of admission based on little or no evidence. Recent attempts to improve our knowledge base by examining the effects of such therapies in small, underpowered studies only add to this lack of certainty by reporting mostly equivalent results within wide confidence intervals. Hence, our clinical practice continues to be uninformed and we may very well be under treating patients by denying them effective therapies simply because we do not know they if are effective or administering therapies that cause harm because we do not know they do cause harm.”34 Conversely, it is important to mention Wakai et al., in a Cochrane review, could not contradict the current recommendation as their review could offer no evidence to alter the current standard use.35

Side Effects and Tolerance

Physicians have a long-term familiarity with nitrates as they have been used in ischaemic heart disease for years, with well-described side effects. This is less so in AHF; however, the existing data suggests a relatively large safety margin. The VMAC study reported headache (in 20 %) and symptomatic hypotension in 5 % as the most common adverse events during the first 24 hours after start of nitroglycerin therapy.15 Apart from these potential adverse events, a major drawback of nitrate therapy is resistance and tolerance. HF patients may be uniquely resistant to nitrates, thus explaining the need for larger than standard doses. To evaluate this possibility, a group of investigators studied femoral artery blood flow velocity differences after nitroglycerin in normal versus HF subjects. They reported attenuated vasodilatory response to IV nitroglycerin in AHF patients that was independent of prior nitrate use, suggesting that an underlying nitrate resistance may affect dosing requirements in AHF patients.36 Beyond baseline resistance, a rapid decrease in initially effective doses, known as tolerance, may occur with nitrates.

The physiology of nitrate tolerance is still unclear. Various hypotheses include that it may be due to activation of neurohormoal systems (i.e., pseudo tolerance) versus a true vascular tolerance, the activation of vasoconstrictive mechanisms in blood vessels, impaired nitroglycerin biotransformation, increased vascular superoxide production, desensitisation of soluble guanylate cyclase or impaired endogenous NO production.37 Which is the dominate cause requires additional investigations. In a recent review of many small studies, Munzel et al. stated that nitrate tolerance is a complex phenomenon caused by abnormalities in the biotransformation and signal transduction of nitrates and by activation of counterregulatory mechanisms.38 However, while tolerance may be a challenge when treating chronic decompensated HF, the fact that it is not seen for several hours makes nitrates suitable for AHF.

Strategies suggested to overcome nitrate tolerance are to increase the dosage, or adding hydralazine concurrently (75 mg four times per day).39 The favourable interaction between hydralazine and nitrates has been demonstrated in the Veterans Heart Failure Trial (V-HeFT) and in the African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT). This study showed beneficial effects on LV function and exercise capacity; most importantly it has been shown to improve survival in large studies in patients with severe heart failure. Although prevention of tolerance is only one of the possible mechanisms to explain the benefit of this combination.40,41 Other strategies to overcome nitrates tolerance is allowing nitrate-free interval. This strategy is more applicable in managing chronic heart failure.42

Potential Future Vasodilator for Acute Heart Failure: Nitrite

It is well documented that patients receiving IV organic nitrate develop haemodynamic tolerance in as little as 4 hours. Nitrite (NaNO2) does not suffer this limitation and thus may have a future therapeutic role. Physiologically, in healthy subjects, NaNO2 selectively dilates pulmonary capacitance vessels and results in a modest reduction in systemic arterial pressure. However, clinical outcomes in AHF with NaNO2 are less clearly defined.

Ormerod et al., reported the first in-human HF efficacy/safety study of short-term NaNO2 infusion. In 25 patients with severe chronic HF, 5 minutes of IV NaNO2 resulted in a 29 % and 40 % decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance and right atrial pressure, respectively, but only a 4 mmHg decrease in mean arterial pressure. They concluded that NaNO2 has an attractive profile during short-term IV infusion, may have favorable effect in decompensated HF and warrants further evaluation with longer infusion regimens.43

Conclusion

A case for the early use of high-dose nitrates in AHF can be made based on the current literature. This is supported by the knowledge of their mechanism of action given the unique combination of microvascular and haemodynamic effects. Consistent with guideline recommendations, in the absence of systemic hypotension, nitrates appear to be a safe and effective. Initial data suggest that when highdose nitrates are used, they are associated with improved symptoms and reduced mortality in AHF patients. Future research is needed to support future clinical adoption.