Heart failure (HF) is a major and growing public health problem with high morbidity, mortality and costs.1 Due to the ageing the population, the mean age of patients with HF is increasing and exceeds 70 years in most developed countries. HF prevalence rises with age and exceeds 10% in people over 80.2 Older patients are more frail and have a higher risk of cardiovascular events. They also have a lower tolerance to medications and a higher occurrence of adverse effects and drug interactions, which may lead to undertreatment and an impaired prognosis.3 Moreover, the effects of evidence-based treatments for HF in terms of outcome have been poorly tested in older patients, and this group is largely under-represented in randomised clinical trials for HF.4,5

Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System Inhibitor Use in Older People

Activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) is a key feature of HF.6 Targeting the RAAS is a cornerstone of the medical management of HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Indeed angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity in people with HFrEF.7–12

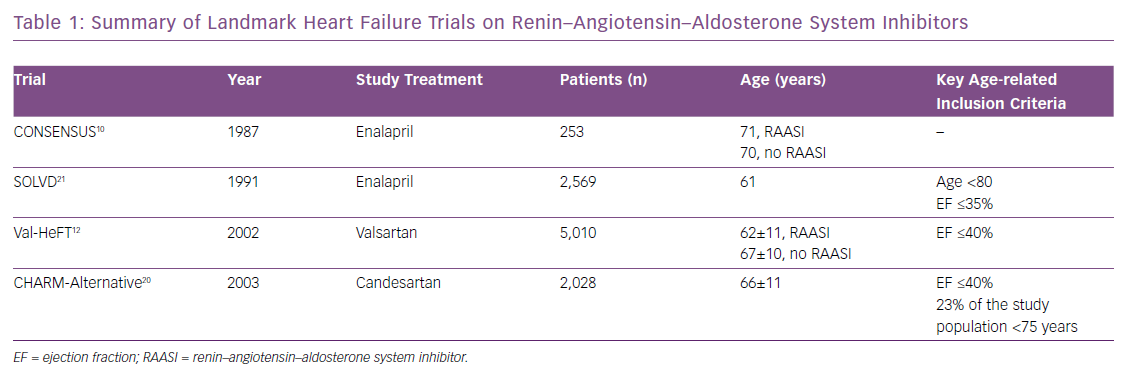

Although older patients represent a substantial HF subpopulation, mean age in HFrEF trials of RAAS inhibitors is 65 years (Table 1). Several reasons may explain the low recruitment of older patients in trials:

- Older patients are less likely to be referred to cardiology care which prevents their enrolment in trials and registries.

- Age is often featured in inclusion/exclusion criterion.

- Age-related co-morbidities, such as chronic kidney disease, may be included in the exclusion criteria.13

In real-world clinical practice, there are major concerns about the underuse and under-prescription of RAAS inhibitors in older adults. In large registry analyses, about 20% of patients aged >80 years have been shown not to receive RAAS inhibitors.14–16 Renal function, perceived risk of dyskalemia, higher chance of drug interactions and side-effects, lower levels of referrals to specialist care and lower expectations of benefits due to a lack of evidence from trials are some of the potential explanations for the reluctance to use RAAS inhibitors in older people compared with younger HFrEF patients. According to the current HFrEF guidelines, RAAS inhibitors are recommended regardless of age.17 Indeed, older adults are at higher risk of cardiovascular events and thus may potentially benefit from HF medications even more than younger patients. However, there is poor evidence to support this.

Impaired Renal Function, Hyperkalemia and Hypotension

Chronic kidney disease, hyperkalemia and drops in systolic blood pressure due to medications are probably the main reasons for the underuse or underdosage of RAAS inhibitors. Despite the protective effect of RAAS inhibitors on the incidence and progression of renal failure, patients with severe chronic kidney disease have been excluded from trials.7,18–21 Chronic kidney disease is a deterrent for RAAS inhibitor prescription in clinical practice.22–24 In a previous dedicated analysis from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry (SwedeHF), including 85,291 patients, focusing on chronic kidney disease, only 66% (n=2410) of patients with HFrEF and eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2 were treated with RAAS inhibitors versus 93% of patients with normal renal function.25 Age was independently associated with renal failure but a propensity score matching analysis showed a similar benefit in patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2 compared with patients without renal failure, supporting RAAS inhibitor use in HFrEF patients regardless of renal function.25 Hyperkalemia has been reported as a main determinant of RAAS inhibitor discontinuation in the inpatient setting in the Get With the Guidelines – Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry.26 In a large US database (with more than 205,000 patients), nearly 60% of HF patients who discontinued RAAS inhibitors due to hyperkalemia experienced an adverse outcome – progression of chronic kidney disease, stroke, acute MI or coronary artery revascularisation or death – compared with 52% of patients on submaximal doses and 44% of patients on target doses. Additionally, patients who discontinued medication had a twofold higher risk of mortality than those on tailored treatment.27 In the SwedeHF study, age was not an independent predictor of hyperkalemia.28

Hypotension is also a frequent reason for underdosing and underuse of RAAS inhibitors.29 Older people are more likely to experience hypotension and subsequent syncope. Careful monitoring, modifications in diuretic strategies and the use of potassium binders may prevent or correct these episodes, avoiding the withdrawal of life-saving therapies. In case of temporary discontinuation, reinitiation or uptitration of therapy should be attempted as soon as safely possible.

Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System Inhibitors and Outcomes in Older Patients

Little randomised data are available on RAAS inhibitor use in older people. A meta-analysis of four HFrEF randomised trials showed ACEIs improved survival in patients aged ≤75 years, but not in those aged >75 years. However, there was no significant interaction between treatment and age and the small sample size of the older subgroup limited the power of the analysis.30 Conversely, small observational studies have reported better survival associated with the use of RAAS inhibitors in older versus younger patients.31,32 In the Euro Heart Failure Survey II, the use of RAAS inhibitors was associated with improved outcome in people in their 80s, even after adjustment for confounding factors.16 A similar conclusion was found by the US National Heart Care project, with the oldest patients (over 85 years) potentially benefiting even more.23 No specific data comparing the efficacy of ACEIs versus ARBs in older patients are available. However, data from meta-analyses as well as comparative trials suggest an advantage of ACEIs over ARBs in terms of cardiovascular mortality but not HF hospital admissions.33–35 Moreover, HF management remains a synergistic approach combining therapeutic regimens. The concomitant use of RAAS inhibitors and beta-blockers is by far the most effective strategy.36 Hence, delays in the initiation of the second drug should be avoided and, according to former comparative studies, beta-blockers may be initiated alone in case of worsening renal function or dyskalemia after introduction of RAAS inhibitors.37,38

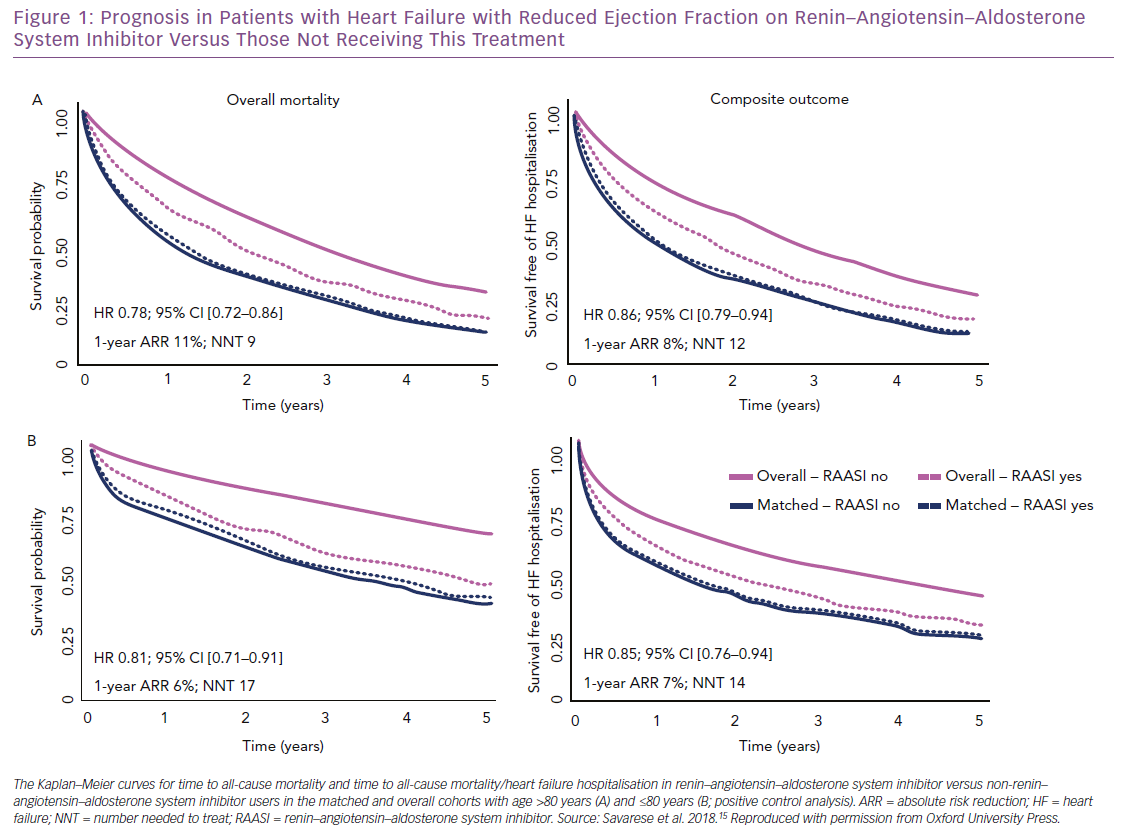

We investigated the association between RAAS inhibitor use and outcomes (i.e. all-cause mortality; the composite of all-cause mortality and HF hospitalisation) in the SwedeHF, which includes one of the largest cohorts of older patients with HFrEF worldwide.15 Of 6,710 HFrEF patients aged >80 years enrolled between 2000 and 2012, 20% were not receiving RAAS inhibitors. After propensity score matching, 1-year and 3-year survival were significantly improved in treated (60% and 32%, respectively) versus untreated patients (49% and 26%). The absolute risk reduction was 11% and nine patients needed treatment to save one life in 1 year. Thus, over a median follow-up of 1.4 years, RAAS inhibitor use was associated with a 22% reduction in risk of all-cause death, which is comparable to what we observed in patients aged <80 years that were used as positive control and in randomised clinical trials testing RAAS inhibitors (Figure 1).10,12,20,21,39 This finding may suggest that similar results could be replicated in a trial setting.

The greater absolute risk reduction observed in our registry analysis in patients aged >80 versus ≤80 years, together with the low proportion of elderly patients receiving >50% of the target dose of RAAS inhibitors (i.e. 53% of our elderly population), may suggest a greater benefit in terms of mortality risk reduction in older versus younger patients receiving RAAS inhibitors. Use of RAAS inhibitors was also associated with a 14% reduction in risk of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalisation (absolute risk reduction 8%, and 12 patients needed to be treated to prevent an event in one year) (Figure 1). Notably, the use of RAAS inhibitors was not associated with increased risk of syncope, which is one of the most important concerns in older patients receiving therapies that lower blood pressure.

Based on the results of the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial, it is now recommended that sacubitril–valsartan replace RAAS inhibitors in patients with HFrEF that remains symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy.17 Impact on outcome, safety profile and cost-effectiveness of this drug in older adults are still poorly known. Among the 8,399 patients recruited in the PARADIGM-HF trial, only 1,563 were >75 years old. In their analysis, Jhund et al found similar beneficial effects from sacubitril/valsartan across the age spectrum. Hypotension, renal impairment and hyperkalemia increased with age in both treatment groups, but the differences between treatment (i.e. more hypotension but less renal impairment and hyperkalemia with sacubitril/valsartan) were consistent regardless of age.40

Unsolved Issues and Future Directions

Older patients represent a majority in the HF population and largely differ from younger patients who are more commonly enrolled in randomised trials. The greater burden of cardiac and non-cardiac comorbidities, frailty and the disease progression expose them to a worse prognosis. The ageing of the population and the increasing prevalence of HF have determined an increasing demand on healthcare resources, leading to a dramatic impact on financial costs. There is a growing mismatch between the characteristics of patients included in clinical trials and those regularly seen in daily practice. Therefore, the medical community should dedicate more efforts toward implementing treatment strategies among older patients with HF. A stricter adhesion to the current evidence-based recommendations and a structured follow-up in dedicated HF clinics with an integrated multispecialty management may be the key to improving outcome in older patients with HF.

Although the limited enrolment of older adults in randomised trials may limit the generalisability of trials’ results in the real-world for older people, increasing evidence from large, unselected registry populations suggests that RAAS inhibitors may be at least as effective in older patients as in younger patients with HFrEF.15,23 However, these findings may be interpreted as a hypothesis which generates randomised trials that investigate this specific issue.