Detailed phenotyping of ventricular–arterial coupling (VAC) and systemic arterial haemodynamics provide important insights into the pathophysiology of left ventricular (LV) energetics, remodelling and fibrosis, and systolic and diastolic dysfunction in various disease states including heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).1

Interactions between the left ventricle, the proximal aorta and the systemic arterial tree encompass a broad and complex set of haemodynamic phenomena. VAC, defined narrowly to encompass the determinants of stroke volume and the energetic coupling of the left ventricle and arterial system, has most frequently been assessed in the pressure–volume plane. This approach provides useful information regarding the mechanical efficiency and performance of the ventricular–arterial system when the LV ejection fraction (LVEF) is frankly abnormal. Analyses in the pressure–volume plane have significant limitations, however, and are less informative in HFpEF. More importantly, analyses in the pressure–volume plane do not characterise broader aspects of ventricular–arterial cross talk, which are clinically relevant among patients at risk for heart failure and for patients with established HFrEF or HFpEF. Assessment of arterial load and VAC via analysis of pressure–flow relations and time-resolved myocardial wall stress provide important incremental physiological information about the cardiovascular system. In particular the systolic loading sequence (early versus late systolic load), an important aspect of VAC, is neglected by pressure–volume analyses, and can profoundly impact LV function, remodelling and progression to heart failure.

This review provides a critical analysis and details of a number of approaches used to assess ventricular–arterial interactions and coupling, with a focus on underlying physiological principles and the interpretation of various indices obtained using non-invasive methods.

The pressure–volume plane

Physiological considerations

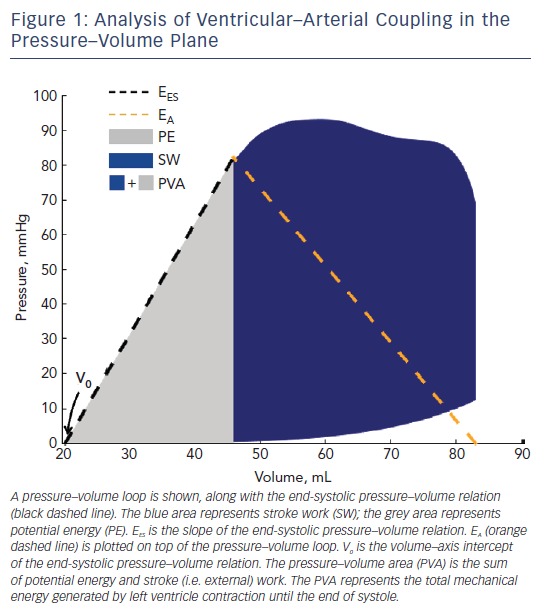

As formulated by Suga and Sagawa several decades ago,2–5 when a ‘family’ of LV pressure–volume loops are obtained from the same subject during acute preload or afterload alterations at a constant inotropic state, the left upper loop corners (end-systolic pressure– volume points) describe the end-systolic pressure–volume relation (ESPVR). The LV end-systolic elastance (EES) is the slope of the ESPVR (Figure 1), which is generally considered to be linear within physiological ranges. In this paradigm, V0 is the volume–axis intercept of the linearly projected ESPVR. V0 represents a purely theoretical LV volume at zero intracavitary pressure, under the assumption of a linear ESPVR. This is, in reality, a false assumption because the ESPVR is markedly non-linear at lower and higher ranges of end-systolic pressure. V0, therefore, can be negative (a physical impossibility) when the ESPVR is projected linearly toward the volume–axis intercept.

EES is an index of the contractility and systolic stiffness of the left ventricle. As such, it is affected by the inotropic state of the myocardium and, in the long-term, by geometric remodelling and biophysical myocyte and interstitial properties.6,7 Although EES is ideally assessed invasively using data from a family of pressure– volume loops obtained during an acute preload or afterload alterations, ‘single-beat’ methods have also been developed8,9 that allow for non-invasive EES estimations using simple echocardiographic measurements. Single-beat methods have undergone limited validation, but are nevertheless broadly used in epidemiological and clinical research due to their ease of use.

For a given beat, the pressure–volume area (PVA) is the area circumscribed by: the end-diastolic pressure–volume relation curve; the end-systolic pressure–volume relation line; and the systolic portion of the pressure–volume loop trajectory (Figure 1).3,10 The PVA in an ejecting contraction that can be divided into two parts: the area within the pressure–volume loop trajectory, which equals LV stroke work (or external work; blue area in Figure 1); and the approximately triangular area enclosed by the end-systolic pressure–volume relation, the left border of a single pressure–volume loop and the end-diastolic pressure–volume relation (grey area in Figure 1), which has been proposed to represent the end-systolic elastic potential energy built up and stored in the left ventricle wall during systole. However, as mentioned above, the left-hand side of this area, corresponding to a linear ESPVR down to its volume axis intercept, is not realistic and substantially differs from the non-linear ESPRV measured at lower pressure ranges.

According to the time-varying elastance paradigm, the PVA represents the total mechanical energy generated by LV contraction until the end of systole. In a single heart operating at a stable contractile state under various preload and afterload conditions, the PVA correlates strongly with myocardial oxygen consumption (MVO2) per beat. Therefore, when studying a single heart operating at a stable contractile state and heart rate, changes in the ratio of stroke work to PVA (which strictly in this context is a good surrogate of MVO2 per beat) are representative of changes in the mechanical efficiency of that heart. Unfortunately, both the slope and the MVO2 axis intercept of the PVA–MVO2 relation vary greatly between individuals.3,10–12 Given the widely varying function that relates MVO2 to the PVA, the ratio of stroke work to PVA is much less informative when comparing the underlying mechanical efficiency between individuals or disease populations. Great caution should therefore be undertaken when interpreting studies in which analyses derived from the pressure–volume plane are used for this purpose.

Given the usefulness of the pressure–volume plane to assess LV function and energetics, an extension of this approach to assess arterial load and VAC was subsequently developed, primarily to study the determinants of stroke volume.13–15 In this paradigm, arterial load is quantified as an ‘effective arterial elastance’, which is defined as the ratio of end-systolic pressure to stroke volume. When arterial load is defined is this manner, the arterial elastance (EA)/EES ratio can be computed as an index of VAC. Due to simple geometric principles, the EA/EES ratio correlates well with the degree to which stroke work and potential energy contribute to the PVA (which, in turn, correlates strongly with the operating mechanical efficiency of a given heart operating at a given heart rate and contractile state). Importantly, the EA/EES ratio is intimately related to ejection fraction (EF=1/[1+EA/EES]); consequently, markedly inefficient ratios are closely associated with the presence of important reductions in LVEF. Abnormal EA/EES has been shown to denote poor operating energetic and mechanical efficiency of the left ventricle, particularly when the LVEF is frankly reduced.1,12–17 This approach is less useful when we want to compare energetic VAC between individuals or to characterise the operating energetic efficiency of the system when the ejection fraction is preserved.

The Pressure–Volume Plane in HFrEF and HFpEF

A reduction of LV chamber pump function (with a reduction of EES), with or without increases in effective EA, results in a high EA/EES ratio, which is accompanied by an increased proportion of the PVA corresponding to potential energy (grey area in Figure 1) rather than external work (blue area in Figure 1), denoting an unfavourable energetic efficiency state. This situation is associated with a reduction in ejection fraction, given the intimate relationship between the EA/EES ratio and ejection fraction. When EES is primarily reduced, therapeutic reductions in EA have the potential to improve the EA/EES ratio (and thus the mechanical efficiency of a given LV–arterial system), but this approach is limited by the minimum mean arterial pressure required for the perfusion of peripheral organs. In hearts with markedly decreased EES, an optimal mechanical efficiency is only achievable at lower mean (and endsystolic) pressures than those required to maintain adequate systemic circulation; operating efficiency is thus substantially decreased relative to the maximally attainable efficiency in order to maintain systemic perfusion. This pathophysiology is characteristic of patients with heart failure with severely reduced LVEF. Interestingly, it has been shown experimentally that both stroke work and efficiency operate at ≥90 % of their optimal values over a broad range of EA/EES ratios (0.3–1.3),17 which corresponds to a wide range of ejection fractions (~40–80 %). Therefore, precise optimisation of the stroke work of the PVA or stroke work relation appears to be of little consequence for energetics in the absence of severe abnormalities in EES/EA (or pronounced reductions in LVEF).17 In severely abnormal coupling states, however, this homeostasis may be lost. For example, in patients with heart failure with severely reduced LVEF these ratios may rise to as high as 4.0 due to the relative decline in ventricular contractile function (lower EES) and often the accompanying high EA. This is clearly suboptimal from the standpoint of ventricular performance and energetic efficiency.

A small study of patients with HFpEF suggested increases in both EA and EES beyond those associated with ageing and/or hypertension.18 However, subsequent studies with larger sample sizes demonstrated that EA and EES were similarly increased in hypertensive controls and HFpEF patients.19,20 Furthermore, patients with HFpEF demonstrate normal energetic ‘coupling’ of the LV (EES) and the arterial load (EA), as assessed in the pressure–volume plane, suggesting that this approach fails to capture key features of the abnormal ventricular–arterial crosstalk in this condition. However, as previously described in great detail,1 pressure–volume analyses can help us understand some aspects of the pathophysiology of HFpEF, including the limited stroke volume reserve, increased blood pressure lability and pre-load sensitivity in this population.1,12,21,22 In particular, subjects with HFpEF have been shown to exhibit a reduced contractile and vasodilatory reserve during exercise, which reduces the “coupling” reserve, as manifested by a less pronounced reduction in the Ea/Ees ratio and a less pronounced increase in EF and cardiac index during exercise.23

Limitations of the Pressure–Volume Plane

Despite its popularity, the pressure–volume plane has important limitations for the comprehensive characterisation of pulsatile arterial load and broader aspects of ventricular–arterial interactions. With each heart beat the left ventricle ejects blood against the hydraulic load imposed by the systemic arterial tree. Given the pulsatile nature of the left ventricle as a pump, arterial load varies over time, is complex and cannot be expressed as a single number.12,22 The EA/EES ratio does not account for time-varying phenomena during ejection,12 thus intrinsically neglecting the LV loading sequence (late versus early systolic load), an important determinant of maladaptive remodelling, hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction and heart failure risk.22,24–29

Importantly, the commonly made assumption that EA is a lumped parameter of resistive and pulsatile arterial load is incorrect.12,30–32 EA is not a true elastance (i.e. the inverse of a compliance) and is almost entirely dependent on vascular resistance (a microvascular, rather than a conduit artery, property) and heart rate.31,33 EA has been shown to be minimally sensitive to (and in some cases to vary inversely with) parameters of pulsatile arterial load.12,30–32 The poor performance of EA in capturing pulsatile arterial load is readily explained by the many simplifying assumptions made during its derivation,12,31,32 which are untenable in the presence of prominent wave reflections.22,34

Time-varying Pressure–Flow Relations

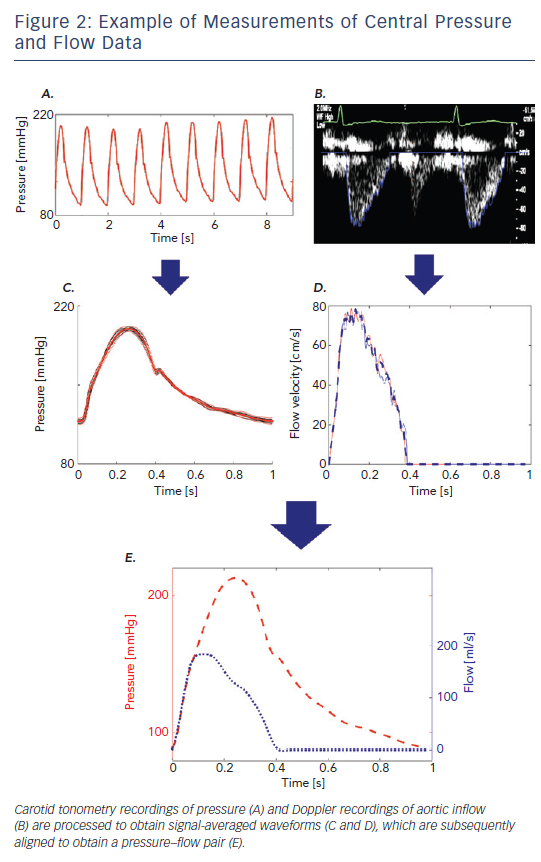

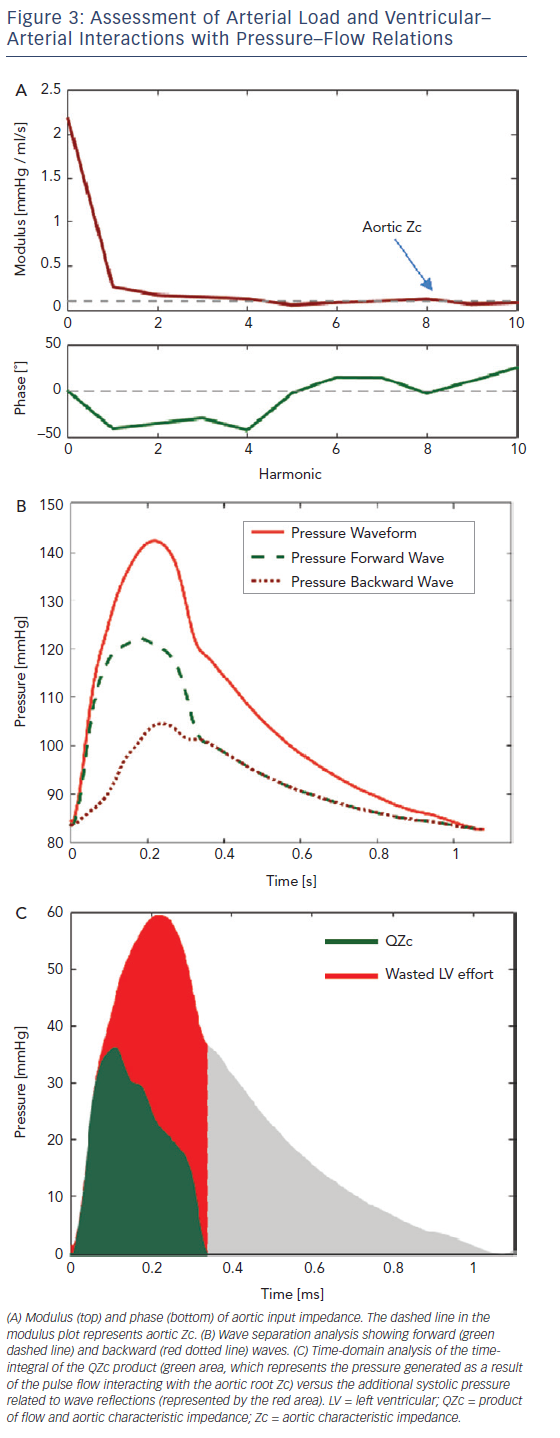

The analysis of time-varying pressure and flow represents a powerful approach for the assessment of ventricular–arterial interactions that overcomes the limitations of the pressure–volume plane. Noninvasive assessment of pressure–flow relations can be accomplished in humans using carotid or radial arterial tonometry35 to measure pressure in conjunction with either Doppler echocardiography or phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging to measure flow. The central pressure–flow relationship can be studied in detail and allows for a comprehensive assessment of LV afterload and VAC.22,36,37 An example of non-invasively obtained central pressure and flow waveforms obtained using carotid arterial tonometry is given in Figure 2A and an example using Doppler echocardiography in Figure 2A. An example of how a pressure–flow pair can be used to assess arterial load and various parameters of VAC in the frequency domain is shown in Figure 3A and how to quantify the effects of wave reflection on the central pressure–flow relation is given in Figure 3B and C.

The Early Systolic Pressure–Flow Relation

In the arterial tree of older adults, a nearly reflectionless state occurs only in very early systole, before the arrival of the bulk of backwardtravelling waves. The slope of the pressure–flow relation during this period is governed by proximal aortic characteristic impedance (Zc). Zc is a local (aortic root) property dependent on the size and stiffness of the aortic root, and is proportional to the product of aortic root crosssectional area and pulse wave velocity. The slope of the pressure–flow relation in early systole closely approximates Zc and can be estimated as the ratio of pressure increase versus flow increase in early systole. Given that wave reflections cancel at high frequencies, aortic Zc can also be measured as the average modulus of input impedance in the frequency domain (dashed line in Figure 3A).

Effects of Wave Reflections

The antegrade pulse wave generated by LV contraction travels in the arteries and is partially reflected at sites of impedance mismatch, such as points of branching, change in wall diameter or change in material properties along the arterial tree. Innumerable reflections merge as they travel back to the left ventricle, where a discrete reflected wave can be observed.22,36,37 The time of arrival of the reflected wave in the proximal aorta depends on the location of reflection sites and on the pulse wave velocity of conduit vessels, particularly the aorta, which transmits both forward- and backward-travelling waves from and towards the left ventricle, respectively.22,38,39 Stiffer aortas (with greater pulse wave velocity) conduct the forward- and backward-travelling waves at greater velocities and therefore promote shorter reflected wave transit times (i.e. earlier arrival of wave reflections to the left ventricle).22,40 In older adults, wave reflections travel quickly, arriving back in the proximal aorta while the ventricle is still ejecting blood in systole. This early arrival of wave reflections increases the mid-to-late systolic workload of the left ventricle and profoundly impacts the LV loading sequence (late relative to early systolic load).

Such early wave reflections are a feature of middle and older age in humans. In young adults, wave reflections return to the left ventricle predominantly in diastole, thus augmenting coronary blood flow, with minimal adverse impact on LV systolic workload. It is worth noting that early wave reflections tend to sustain systolic pressure in mid-to-late systole, which may occur with or without pronounced increases in peak systolic pressure. Central systolic pressure, pulse pressure and pressure augmentation, although influenced by wave reflections, are therefore not adequate measurements of the magnitude of wave reflections or their effects on LV workload. Furthermore, aortic pressure augmentation is confounded by multiple factors, including the LV contractility, temporal pattern of LV contraction and preload.41 Wave reflections and their physiological effects are best assessed via analyses of pressure–flow relations.

Net pressure and flow measured at the aortic root result from the sum of the forward wave, which affects pressure and flow in the same direction, and the backward-travelling wave, which has opposing effects on pressure and flow. Since the backward wave increases pressure relative to flow, its effects are readily apparent from visual inspection of the pressure–flow pair, when pressure and flow are scaled according to the aortic root Zc (Figure 2, bottom panel). Alternatively, the product of flow and aortic Zc (QZc) can be computed and displayed in units of pressure to demonstrate the effects of wave reflections (green area, Figure 3C). When wave reflections are absent in systole, measured systolic pressure equals the QZc product; whereas in the presence of wave reflections, systolic measured pressure is greater than the QZc product (red area, Figure 3C). We hereby refer to the difference between measured pressure and the QZc product as ‘wasted LV effort’, which is analogous to the concept originally proposed using pressure-only approaches.42,43 As will be further discussed below, this difference is proportional to the net effects of wave reflection on the systolic pressure profile (being equal to twice the systolic portion of the backward pressure wave; Figure 3B and C).

An important but commonly unrecognised fact is that the heart itself is also a reflector.44,45 Backward-travelling reflected waves can re-reflect at the left ventricle during systole, becoming part of the forward wave. The forward wave is therefore influenced by wave reflections, just like the backward wave is a function of the forward wave. Re-reflections are also present in diastole, because backward-travelling waves re-reflect and rectify at the aortic valve. This is why a forward wave is always present in diastole, despite the cessation of LV ejection.

When stroke volume is normal, the QZc product can be interpreted clinically as an indicator of the degree of mismatch between aortic root properties (size and stiffness) and systemic flow requirements. Mismatch may be due to an abnormally increased Zc (which may contribute to increased pulse pressure with ageing and various disease states) or increased flow requirements (i.e. thyrotoxicosis). However, an abnormal QZc product may also be a consequence of a reduced (e.g. HFrEF) or increased (e.g. aortic insufficiency) stroke volume (and pulse volume flow) in the absence of changes in systemic flow requirements or in aortic Zc. It is important to recognise that the forward pressure wave exceeds the QZc product by an amount equal to the backward wave. Forward pressure wave amplitude, therefore, cannot be interpreted purely as an index of mismatch flow needs and aortic root properties, because it also contains contributions from wave re-reflections.44

The difference between measured pressure and the QZc product can be interpreted as the pulsatile pressure that is not primarily required to promote pulsatile systolic flow through the aortic root Zc, but is necessary to overcome the effect of wave reflection. An analogous concept was originally proposed by Hashimoto, Nichols and O’Rourke and called ‘wasted LV effort’, using pressure-only approaches.42,43 This principle can be extended to the pressure–flow pair, as shown in Figure 3C (red area).

A popular approach to characterise wave reflections is to compute reflection magnitude as the ratio of the amplitude of the backward wave over the forward wave (Pb/Pf). This computation, however, can underestimate the effects of reflections on pressure (and LV load) because, as stated above, peripheral reflections that re-reflect at the heart become part of the forward wave, adding to the denominator rather than solely the numerator of reflection magnitude. Similarly, reflection magnitude does not contain information about the timing of the reflected wave and its net effect on aortic (and LV) pressure in systole. Furthermore, this ratio can be impacted by the time pattern of LV contraction for any given input impedance of the systemic circulation. In many instances it therefore becomes particularly important to pay attention to indices such as QZc and the difference between total pressure and QZc during systole, in addition to more detailed analyses of pressure–flow relations (and the effects of wave reflections) in the frequency domain. In particular, reflection coefficients computed in the frequency domain are entirely derived from the input impedance spectrum, and are therefore more ‘pure’ indices of arterial load. The reader is referred to previous publications for more detailed descriptions of pressure–flow relations in the frequency domain.22,37,46 Frequencydomain analyses tend to be considered complex for intuitive clinical assessments, but remain extremely valuable for mechanistic clinical research studies.

Effect of Wave Reflections and Late Systolic LV Load on LV Remodelling, Hypertrophy and Heart Failure Risk

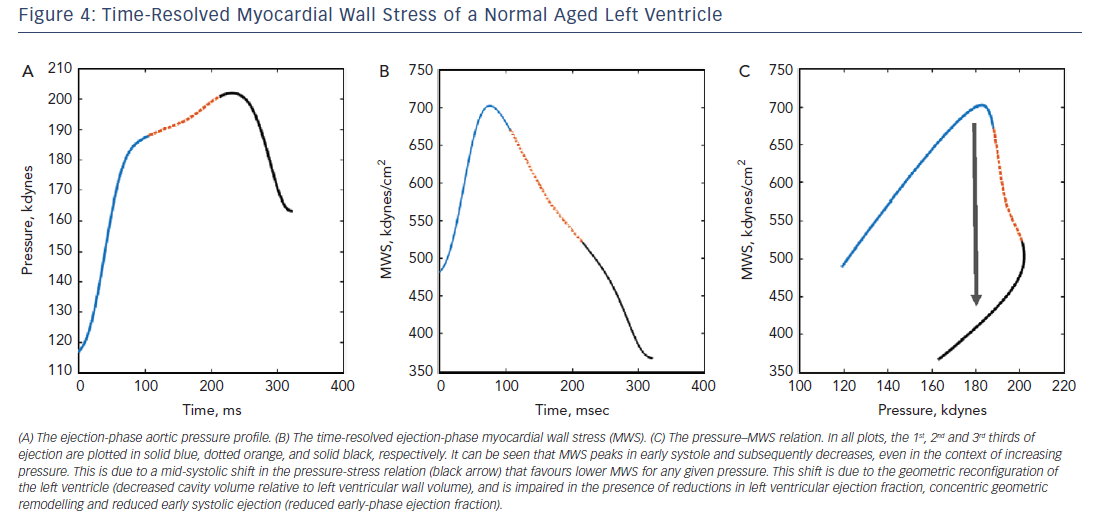

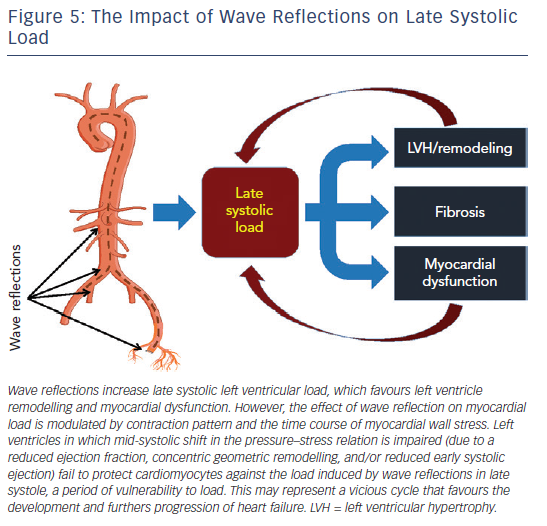

For any given level of systolic blood pressure, prominent latesystolic loading has been shown to exert deleterious effects on LV structure and function in animal and human studies (Figure 4).22,26,28 Late systolic load from wave reflections has been shown to induce LV hypertrophy and fibrosis in rats.26 Accordingly, a relationship between reflection magnitude and LV mass measured with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging has been reported in community-based studies,47,48 and changes in wave reflection magnitude occurring during antihypertensive therapy are associated with the regression of LV mass independently of the reduction in blood pressure.27

Wave reflection also plays a role in diastolic dysfunction. Canine studies have shown that for any given increase in LV pressure, late systolic LV loading induces greater impairment of LV relaxation than early systolic loading.28 In support of these experimental findings demonstrating a cause and effect relationship between late systolic load and impaired relaxation, human studies demonstrate that indices of late systolic load are independently associated with diastolic dysfunction,23,25,49–51 left atrial remodelling50,52,53 and longitudinal systolic dysfunction.54 A more direct quantification of the myocardial loading sequence can be accomplished by measurements of time-resolved ejection-phase myocardial wall stress (Figure 4). Time-resolved wall stress integrates the impact of prevalent arterial load, including chronic changes in LV structure and function, and the LV contraction pattern, on the myocardial load. Wave reflections selectively increase late systolic wall stress, which is in turn associated with impaired relaxation.29,55 Interestingly, the LV contraction pattern can modulate the influence of wave reflections on late systolic myocardial load. Normally, a marked mid-systolic shift in the relationship between LV pressure and myocardial wall stress (pressure–stress relation) occurs as a result of LV contraction (Figure 5). This shift effectively protects LV cardiomyocytes against excessive wall stress in late systole, a period of increased vulnerability to the ill effects of load. During late systole, several cellular processes may operate to mediate myocardial dysfunction and remodelling. Abnormalities such as reduced early-phase ejection, a lower LVEF, and concentric hypertrophy/remodelling, can impair the mid-systolic shift in the pressure–myocardial wall stress relation, making the left ventricle more susceptible to the effects of wave reflections on the myocardium.56,57

Consistent with the effects of wave reflections on LV remodelling, fibrosis and dysfunction, wave reflection magnitude (the ratio of backward to forward wave amplitude) and late systolic hypertension have been shown to strongly predict incident heart failure in the general population.56,58,59 These studies did not distinguish between incident HFpEF and HFrEF.

Wave Reflections and Pressure–Flow Relations in Established HFrEF and HFpEF

When LV pump function is preserved, the reflected wave typically induces a late systolic pressure peak in the pressure waveform, augmenting aortic pressure in mid-to-late systole.22 These features are prominent in patients with HFpEF.25,60,61 When LV pump function is reduced, however, wave reflection may exert more pronounced effects to decrease flow, with no apparent alteration in the appearance of the pressure waveform (when the latter is analysed in isolation). It is therefore important to measure both pressure and flow in order to properly measure and interpret wave reflections (particularly in patients with impaired LV systolic function). In patients with severe LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF ≤30 %), wave reflections truncate flow, reduce stroke volume and induce a shortening of ejection duration.62 In addition, the magnitude of wave reflection, which is normally reduced during exercise, may exhibit abnormalities in heart failure. Patients with HFrEF secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy have been shown to demonstrate an impairment in the reduction in wave reflections during exercise, with a smaller reduction in wave reflections for any given reduction in systemic vascular resistance, compared to normal controls.63 This could increase myocardial work during exercise and contribute to exercise intolerance. Changes in wave reflection during exercise have not been studied in HFpEF.

Therapeutic Approaches

In HFrEF, nitroprusside has been shown to reduce wave reflections at rest and during exercise.64 Interestingly, inotropic therapy with dobutamine, but not dopamine, can simultaneously increase inotropy and reduce arterial load in HFrEF.65 In advanced HFrEF, reduced blood pressure and vasodilation by current standard pharmacological therapy may substantially reduce arterial load and wave reflections, leading to improved VAC. Interestingly, in post-transplant patients, these effects of standard heart failure therapy are eliminated over a short time period. In this setting, heart transplant recipients with antecedent ischaemic cardiomyopathy demonstrated increased markers of wave reflections compared with non-ischaemic heart transplant recipients.66 It is unclear, however, whether this is due to differences in ‘residual’ (post-transplant) therapy (such as vasodilators for hypertension) and/or to the presence of atherosclerotic plaques in conduit arteries that may serve as sources of wave reflection.

Consistent with newly-described normoxic activation of nitrite in conduit arteries,67 inorganic nitrate has recently been shown to reduce wave reflections in patients with HFpEF,61 and has demonstrated promising effects on exercise capacity and quality of life in phase IIa studies in this population.61,68,69 Larger phase IIb trials are currently being performed.70 Organic nitrate, in contrast to inorganic nitrate, has been shown to exert deleterious effects in this patient population. In the Nitrate’s Effect on Activity Tolerance in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (NEAT-HFpEF) trial, isosorbide mononitrate caused a dose-dependent reduction in physical activity.71 In another recent trial, isosorbide dinitrate, with or without hydralazine, did not exert beneficial effects on wave reflections, LV remodelling or submaximal exercise in HFpEF and was poorly tolerated. Furthermore, combination therapy with isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine actually increased wave reflections, reduced submaximal exercise capacity and increased the native myocardial T1, suggesting deleterious effects on myocardial remodelling.72 Effects of systemic nitrates or B-type natriuretic peptide to improve reflected waves may be countered by the effects of these compounds on preload, leading to a net reduction in stroke volume and an overall unfavourable haemodynamic response.41

Conclusion

Although the pressure–volume plane remains the gold standard to assess left ventricle chamber pump function in a load-independent manner, it has serious limitations for the assessment of pulsatile arterial load and VAC, particularly in HFpEF. Comprehensive assessment of pulsatile arterial load and ventricular–arterial interactions can be achieved with analyses of pressure–flow relations. Despite the apparent complexity of pressure–flow analyses, this approach can be implemented at the bedside and can be highly informative in clinical research and potentially in clinical practice. Wider application of methods to characterise ventricular–arterial interaction should be incorporated into the design of clinical trials. Such mechanistic heart failure studies are critical, particularly in HFpEF, and may ultimately lead to effective therapy for this condition. Eventually, assessments of individual patients may facilitate the application of tailored (personalised) therapeutic approaches in the era of precision medicine.